Ian Badgley

Overview

Introduction

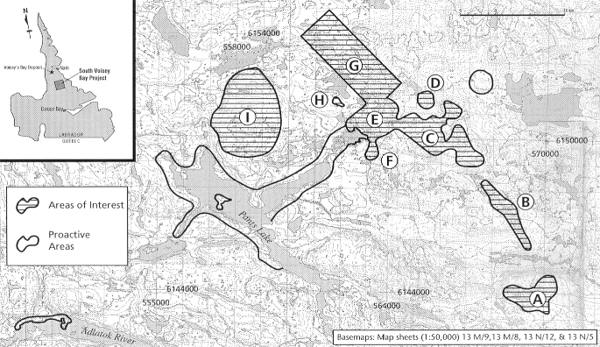

The present report concerns the Stage 1 Historic Resources Overview Assessment conducted in the South Voisey’s Bay Project area, interior central Labrador (Figure 1). Its overall purpose was to identify and assess the historic resources potential or sensitivity within a study area encompassing a portion of a mining block. It was also intended to lay the base for the development, if necessary, of an appropriate methodology for a detailed Stage 2 assessment of potential mining exploration impacts on these resources.

Figure 1. South Voisey’s Bay Project Study Area.

Objectives

A two-tiered approach integrating impact assessment with proactive research was applied to the Stage 1 reconnaissance. The principal component was focused on the survey of gridded areas of interest defined on the basis of geological and and geophysical studies. Its main goals were to identify and assess historic resources in these areas and to evaluate the potential impacts of drill programs and other mineral exploration work on these resources. Another objective was to identify areas where historic resources are apparently absent, implying low or no archaeological potential.

The proactive component was centred on the survey of selected localities removed from the defined areas of interest. This component was organized in large measure on the basis of Innu land use and occupancy data provided by the Innu Nation. Its objectives were to gain a better understanding of the overall archaeological potential of the territory covered by the South Voisey’s Bay Project, and to identify zones of cultural sensitivity within this territory. The confirmation of Innu campsites reported in the vicinity of Pants Lake (known to the Innu as Kakashipishuneakamats) was of major importance to these objectives.

Methodology

The field reconnaissance was preceded by a review of the archaeological and ethnographic literature relelevant to the project area, including available Innu land use and occupancy data. This background research was undertaken in order to clarify past settlement patterns and site locations in interior Labrador. Its aim was to identify the characteristics of locations most likely to contain historic resources in the study area.

The survey was ground-based and conducted on foot. Survey areas removed from Pants Lake were accessed by helicopter while others located along the Lake’s shoreline were accessed by zodiac. Each area of interest was initially overflown at low altitude, in order to determine the strategy best suited to maximum surface coverage and to allow locations of apparent potential to be identified. Most of the areas were surveyed in systematic transects, usually at intervals ranging from 50 to 100 m. The two largest areas of interest were exceptions. In these instances, attention was generally directed toward particular localities judged to be of historic resource potential (e.g., the margins of streams and ponds). This judgmental approach was also applied to the survey’s proactive component.

Survey activities included intensive surface inspection and subsurface sampling. Test pits varied from 25 x 25 cm to 50 x 50 cm in dimensions and were randomly excavated at various locations throughout the areas surveyed. Potential drill holes included in the assessment were systematically sampled at intervals of 2 to 5 m, to a distance of approximately 50 m from each hole. All test pits were excavated into subsurface soil horizons deemed to be culturally sterile.

Each archaeological site identified was intensively surface-inspected. However, no artifacts or cultural materials were surface-collected and no subsurface sampling was carried out in any of these sites. This decision was taken in order to preserve the physical integrity of these sites for more detailed research in the future, and to maximize the time available for the survey.

Survey Summary

Survey activities extended beyond the grids in all areas of interest and covered the terrain between most of these grids. These activities stressed maximum surface coverage and allowed for thorough assessment of the historic resource potential in each of these areas, including the two largest. Survey of the latter areas was carried out over a 5 day period and included all locations that can reasonably be expected to contain historic resources. In addition to random subsurface sampling, a total of 142 test pits were systematically excavated at 15 potential drill holes located in three grids. All test pits were negative, yeilding no cultural material or other indications of past occupation. As well, no historic resources were observed on the surface in any of the areas of interest.

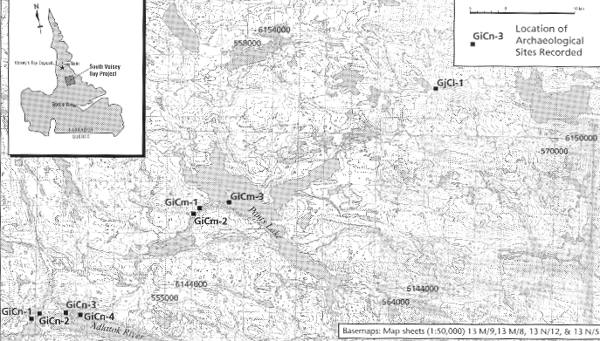

Eight new archaeological sites were identified during the survey (Figure 2). One of these sites, GjCl-1, is situated about 50 m from the edge of an area of interest. This site is defined by a single Innu tent camp, probably dating to the first half of the 20th century.

The seven other sites are located in the survey’s proactive component. These sites include GiCm-2, composed of a partially collapsed cairn situated at the outlet of a small pond draining into Pants Lake, and GiCm-3 comprising a boulder shelter located on the south point of the island in the lake. The first of these sites is tentatively interpreted as prehistoric Inuit in origin. GiCm-3 is of undetermined prehistoric cultural affiliation.

GiCn-4 consists of an extensive Innu campsite on the north bank of the Adlatok River. Estimated to date to the 1800s or early 1900s, this campsite is composed of a sweat lodge, four tent camps and two large concentrations of fire-cracked rocks. Several sled crossbars, two runners and numerous other fragments of worked wood were observed on the surface of GiCn-4.

Four sites are defined by axe-cut tree or willow stumps, all of which appear to date to within the last 50 years. One site, GiCn-1, occurs a short distance from the cairn site on the same stream. The three remaining sites are located on the north bank of the Adlatok River, west of the large Innu campsite. At least two of these sites (GiCn-2 and GiCn-3) appear to correspond to campsites indicated in the Innu land use and occupancy data. Attempts to confirm other campsites identified in these data as well as two Innu camps recorded by earlier archaeological research at Pants Lake were unsuccessful.

South Voisey’s Bay Project

Study Area

The survey study area is centred on Pants Lake and the surrounding southwest portion of the project (Figure 1). Its principal component comprises 9 areas of interest incorporating 13 grids located to the east and northeast of the Lake. These areas consist of a series of bedrock ridges and hills extending in a broad arc toward the northwest. The elevation of the hill summits increases correspondingly, from roughly 450 m in the east to 580 m in the northwestern section. Most slopes are moderately steep or excessive, and are frequently interrupted by cliffs. The intervening valleys are relatively shallow, situated around 300 m in elevation, and are covered by till and outwash rubble. These lower elevations are usually wet, containing large colonies of sphagnum moss and dense forest. A large portion of the eastern part of the study area has been burned over.

The proactive component included survey of the northeast and northwest arms of Pants Lake, the greater part of the Lake’s southwestern shoreline, the island, and a small pond and outlet emptying into the lake near the island. A 2 km section of the north bank of the Adlatok River southwest of Pants Lake was also surveyed. Field activities in these areas were generally restricted to within 100 m of the Adlatok, and to elevations below 30 m (Figure 1).

Study Area

Two historic resources overview assessments were carried out in the South Voisey’s Bay Project area in 1995. One of these assessments, conducted by Doug Robbins (1995), was centred on three proposed drill holes on the northwest corner of Pants Lake and the location proposed for a base camp on the southwest shore of the Lake. This survey was also intended to confirm three sites reported by Innu informants.

Although no historic resources were identified at the drill sites, two new Innu camps were recorded. These sites are defined by a tent camp, situated near the base camp location, and several poles interpreted as a marten trap, located at the mouth of the outlet south of the island. Both sites are estimated to have been used within the past 50 years. Two of the reported campsites, comprising a tent camp and axe-cut stumps, were also confirmed.

The other survey was carried out by Gerald Penney (1996). This work was focused on the assessment of 8 potential drill holes at various locations and a proposed drill camp on the northeastern extremity of Pants Lake. Axe-cut stumps were observed in the latter location. No historic resources were identified at any of the potential drill holes.

Land Use and Occupancy in Central Labrador

Culture-History

Archaeological research in the coastal region of central Labrador has revealed a complex sequence of Indian and Inuit occupations spanning some 6500 years. This region was initially occupied by groups of the Maritime Archaic tradition, who spread north from southern Labrador around the middle of the fifth millenium B.C. This tradition was succeeded by the Early Palaeo-Eskimo pre-Dorset culture (3800-2200 B.P.), Intermediate Indian Period complexes (3500-1000 B.P.) and the Late Palaeo-Eskimo Dorset culture (2500-650 B.P.). Late Period Indian groups of the Point Revenge complex occupied the coast from 1000-400 B.P. and were followed by the neo-Eskimo Thule culture, arriving in the northern part of the region around 700 years ago. The Point Revenge peoples are culturally linked to the historic Innu (Montagnais/Naskapi) and the Thule groups are the direct ancestors of the Labrador Inuit.

In contrast to the coastal region, interior Labrador is poorly understood archaeologically. However, sites at Indian House Lake, on the George River in Quebec, indicate that the interior was initially occupied by Archaic groups sometime between 3500 and 3000 B.P. (Pilon 1982, Samson 1978, 1981). As summarized by McCaffrey (1989:73), interior occupation over the subsequent 2000-1500 years apears to have been continuous in some areas and sporadic in others, followed by increasingly widespread and continuous use of the territory beginning about 1500 B.P.

Interior Occupations

Archaeology Review

The greater part of past archaeological research in interior Labrador has been limited to generally brief surveys of varying scope (c.f. MacLeod 1967, 1968, Fitzhugh 1972, McCaffrey 1989, McCaffrey, Loring and Fitzhugh 1989, Thomson 1984, 1985). Much of this work was focused on prehistoric research and yielded comparatively few archaeological sites.

More recently survey work conducted by Biggin and Ryan (1989) in the Strange Lake area resulted in the registration of 33 sites in the upper reaches of Anaktalik Brook, Konrad Brook, and Kogaluk River drainages. One of these sites is tentatively interpreted as Maritime Archaic in affiliation, two appear to be related to the Point Revenge complex and nine are of unknown prehistoric affiliation. Most of the remaining sites are Innu camps, some of which may date to the 19th century, while several others might be Inuit.

As well, McAleese (1993) reports 30 recent Innu sites and 6 prehistoric sites at Pocket Knife, Croteau and Snegamook Lakes in the Kanairiktok River basin. Lithics collected at one of the prehistoric sites compare closely with certain raw materials associated with the Intermediate Indian Saunders complex (3500-2800 B.P.). The cultural affiliation of the other prehistoric sites is unclear.

Ethnography

The interior woodlands of Labrador represent the traditional territory of the Innu (c.f. Tanner 1944, Leacock 1969). Use of this vast inland plateau reflects a general pattern of seasonal resource exploitation extending through prehistory into the ethnographic present. Labrador Inuit use of the interior north of Voisey’s Bay is also documented to as early as the 18th century (c.f. Taylor 1977). As noted by Fitzhugh (1977:35), Inuit penetration of more southerly inland areas remains obscure.

Speck (1933) identified individual Innu bands with separate hunting territories in interior Labrador. Loring (1992, cited in Penney 1996:5) considers these ‘band’ distinctions to result from Innu settlement at Schefferville, Davis Inlet, and Ungava due to increased economic dependence on caribou hunting over the period 1350 to 1900. Regardless, all Innu bands hunted the George River basin during this period and followed a basically similar settlement-subsistence pattern.

This pattern involved extensive travel mobility based on interior caribou hunting and fur trapping during fall, winter and spring, and coastal sealing, fishing, and bird hunting during summer. Fish were an important secondary resource in the interior, complemented by black bears and small game. Travel inland was by means of networks of interconnected lakes, ponds, and streams forming relatively narrow corridors centred on major river valleys. Main caribou hunting territories accessed by these travel routes included the area between Border Beacon and Lake Mistassin and the adjacent George River drainage.

Fitzhugh (1972:51) describes Innu use of the interior as involving a cycle of seasonal band aggregates and dispersal. The principal settlement types associated with this cycle include fall and winter caribou hunting camps occupied by several families, bivouac camps used by hunters or travellers, and spring gathering sites, which later included mid-winter congregations. These large sites averaged 50 to 100 individuals and served as central base camps for social activities, fishing, and bird and small game hunting. Trapping camps were probably not part of the prehistoric settlement types, but appear to have developed following contact with Europeans. These camps consisted of more permanent habitations occupied by single families. Trapping was most intensive during early winter and was followed by transitory caribou hunting beginning in late January. Excluding occassional bivouacs on the exposed uplands, all settlements were normally situated in sheltered locations at low elevations, often within the edge of the forest.

Increased emphasis on fur trapping and greater reliance on trade goods throughout the second half of the 19th century resulted in significant alterations to the traditional Innu settlement-subsistence pattern. Additional changes were caused by the expansion in the early 20th century of non-aboriginal trappers into the best trapping grounds, thereby reducing the traditional territory of the Innu. This steady expansion, coupled with the economic establishment in the communities of permanent government institutions and services in the 1950s, culminates in the more sedentary lifeway of the modern Innu.

Figure 2. Location of Archaeological Sites Recorded.

Archaeological Site Descriptions

GiCm-1

The site consists of two axe-cut willow stumps bordering a bedrock ledge on the west side of a stream emptying into the northwest quadrant of Pants Lake, slightly southwest of the island. It is situated on the edge of a caribou trail, approximately 300 m from the stream mouth. The stumps are 50 cm in height and estimated to date to the 1950s or later.

GiCm-2

The site occupies a narrow gravel ridge on the west side of the same stream as GiCm-1, near the outlet of a small pond roughly 1 km southwest of Pants Lake. The gravel formation is situated approximately 50 m west of the stream and 70 m north of the pond. The ridge is about 55 m in length and 15 m in maximum width at its northern extremity. Its elevation above the level of the pond decreases from 15 m in its northern section to 10 m at its southern tip. The ridge is crossed by 2 caribou trails.

GiCm-2 is defined by a partially collapsed cairn, located at the northern extremity of the ridge. The intact portion of the feature is 55 cm in height and consists of a single block perched on a boulder. Three toppled flagstones and an angular cap rock border the west side of the boulder. The original standing height of the cairn would have been 85 cm.

Heavy lichen-welding of the toppled stones suggests a minimum of 200 years for the collapse of the cairn. As stone-built cairns are a common element in Palaeo-Eskimo and neo-Eskimo sites, a prehistoric Inuit cultural affiliation is tentatively interpreted for GiCm-2.

GiCm-3

GiCm-3 consists of a boulder shelter and exterior feature located on the south tip of the island in Pants Lake. The shelter is located about 50 m from the shoreline, in the centre of a deposit of large angular boulders. This deposit is situated on a low, rounded bedrock outcrop approximately 7 m above the lake level.

The shelter is formed by two halves of a large cleft boulder, measuring 1.1 and 1.4 m in height. The opposing surfaces of these halves are separated by a corridor forming the interior of the shelter. This corridor is 2.4 m in overall length, oriented northeast-southwest. Its southern extremity is 80 cm wide and expands to 1.1 m at its northern end. This end is protected by large boulders, which, together with smaller rocks placed against the eastern half of the shelter, create a 1 m wide passage opening toward the west. A similar passage, 65 cm in width and 2 m long, extends along the southern edge of the eastern half of the shelter. Several rocks have also been placed in this passage.

The shelter contains a rock-built hearth located in the northeastern section of the corrider, against the boulder face. The hearth consists of several courses of small flagstones and rocks placed laterally on a thick slab forming the hearth base. This feature measures about 20 cm in height and 1.1 m in overall length, with interior dimensions of 35 x 25 cm. A number of flagstones and rocks are scattered around the hearth.

The exterior feature comprises a small concentration of rocks situated 30 m northeast of the boulder shelter. This feature measures 35 x 55 cm and is of unknown function.

Thick lichen growth on the rocks in the interior hearth suggests prehistoric use of the boulder shelter. The cultural affiliation of the site is unknown.

GiCn-1

GiCn-1 is located on the north bank of the Adlatok River, at the western end of a broadening of the river, approximately 8 km southwest of Pants Lake. The site is defined by three axe-cut tree stumps situated on the first terrace, at an elevation of 5 m. The stumps range in height from 70 cm to 1.4 m and are estimated at 50 years. The site appears to correspond to a campsite indicated by Innu land use and occupancy data.

GiCn-2

The site is defined by a single axe-cut tree stump situated on the 5 m terrace on the north bank of the Adlatok River, about 250 m east of GiCn-1. The stump is 2 m in height and estimated to have been cut within the past 50 years. The site appears to correspond to a second campsite indicated by Innu land use and occupancy data.

GiCn-3

GiCn-3 is defined by two axe-cut tree stumps located on the 5 metre terrace on the north bank of the Adlatok River. The site is situated near the foot of a lagoon-like bay on the west side of a relatively broad point. The stumps are 75 cm in height and appear to have been cut within the past 50 or 60 years.

GiCn-3 approximates the location of a third campsite reported in Innu land use and occupancy data. However, this site may be related to an old outfitter’s camp which was located on the bay on the west side of the point. The remains of this camp include a 10 m long dock, a delapidated plywood shed, a large plywood shed, a large plywood floor, traces of 5 tents, log-lined paths, several 45 gallon drums and numerous scattered sheets of plywood.

GiCn-4

GiCn-4 is a large Innu campsite located on the north bank of the Adlatok River, about 500 m east of GiCn-3. The main component of the site is situated in a clearing on the 5 m terrace on the east side of the point, roughly 300 m from the old outfitter’s camp. This component consists of a sweat lodge, 4 tent camps, and associated activity areas distributed over a surface area of approximately 1000 m2.

Structure 1, the sweat lodge, and Structures 2 and 3 (described below) are aligned over a distance of 25 m along the east edge of the terrace. The sweat lodge is defined by a slight, rectangular depression bordered by a low, raised rim 20 to 30 cm in width. The structure is oriented north-south and measures 2.8 x 4 m in interior dimensions. It contains a cobble hearth, measuring 0.8 x 1.1 m, a number of associated fire-cracked rocks, and several pieces of wood, some of which are burnt. A low earthen ramp about 8 cm in height, extends between the hearth and the structure’s entrance. The ramp is 0.7 m long and flares in width from 0.8 m at the hearth to 1 m at the entrance. The entrance is defined by a log, 1.8 m in length, placed on the west side of the structure. Two collapsed stove supports, each 15 cm in length, occur 70 cm northwest of the entrance.

Structure 2 is defined by a subrectangular depression situated 2.5 m northwest of the sweat lodge and about 4 m west of the terrace edge. The western portion of the structure has been excavated into a low embankment and is bordered by a pronounced rim. The interior of the structure measures 1.7 x 2.3 m and contains 4 stove supports, 2 of which are still in place. These 4 supports are situated toward the rear, or western section of the structure, and delimit a rectangular space 20 x 40 cm. Several fire-cracked rocks are associated with the stove supports, and wooden poles are scattered both in and around the structure.

Structure 3 is located 6 m north of Structure 2 and measures 2 x 2.5 m in interior dimensions. This third structure is also defined by a subrectangular depression, with the western portion being excavated into a low embankment. A collapsed stove support, a sled crossbar 60 cm in length, and several poles are associated with Structure 3. Three axe-cut tree stumps occur 8 m north of the structure.

Structure 4 is located 12 m southwest of the sweat lodge. This tent camp is defined by 4 poles and a tent peg covering an area of roughly 4 m2.

Structure 5 is situated 8 m west of the sweat lodge and measures 2.5 x 4 m with the longer axis oriented generally north-south. The perimeter of this tent is defined by an in-place tent peg, another tent peg lying on the surface, and poles and a number of worked pieces of wood enclosing an area relatively free of wood chips and other fragments. Worked items include a sled front crossbar, a fragment of a second crossbar, and the front portion of a sled runner. The runner fragment is associated with an exterior woodworking area on the eastern periphery of Structure 5. This area is defined by numerous fragments of worked and unworked wood distributed over approximately 6 m2.

Two large concentrations of fire-cracked rocks were also noted roughly 100 m northwest of Structure 5. These concentrations are separated by a distance of 6 m and measure 1.2 x 1.5 m and 1.1 x 1.4 m, respectively. As well, an intact sled runner, 1.3 m in length, was found on the terrace slope east of the sweat lodge. This runner was removed to a protected location near Structure 5 in order to prevent its loss due to ice-rafting or high water levels.

Multiple occupations are suggested for GiCn-4, dating possibly from the mid-19th century to the first quarter of the 20th century or later.

GjCl-1

GjCl-1 is located on a slightly raised gravel deposit on the north side of a small stream about 3 km northeast of the northeast arm of Pants Lake. It is situated in a clearing approximately 100 m east of the outlet of a pond, at an elevation of about 250 m and roughly 50 m north of the limit of the area of interest designated “D.”

The site consists of a single Innu tent camp, measuring 2.8 x 3 m. The camp is defined by a shallow depression delimited to the north by a low, raised rim, and to the east, by a large, split boulder. The entrance is marked by two standing poles on the west side of the depression and is 70 cm wide. These poles are 0.5 to 1.6 m in height, and are associated with three flagstones. A number of tentpoles are scattered around the camp, with several others stacked against the boulder at the rear of the structure. The rusted lid of a tin can was noted in the structure and a snowshoe frame was observed embedded in the moss 50 cm south of the camp. This frame is 60 cm wide and 50 cm in length. A possible hearth is situated about 2.5 m south of the structure.

GjCl-1 is estimated to have been used within the past 50 years, if not later.

Archaeological Potential of the South Voisey’s Bay Project Area: A Preliminary Assessment

Recorded sites attest Archaic and later prehistoric occupation of major interior caribou hunting grounds adjacent to the South Voisey’s Bay Project. As well, the Adlatok and Notakwanon drainage systems flow through environmentally similar territory and provide direct access to these hunting grounds. These data combine to suggest a comparable antiquity and density of prehistoric occupation of the project area, in addition to documented historical seasonal use by the Innu.

McAleese (1993:51-52) notes that the few prehistoric sites recorded in the Kanairiktok drainage area reflect the difficulties of surveying forested lakeshores and riverbanks. At the same time, he speculates that the highlands may have been more heavily used than lower areas during prehistory and recommends systematic high elevation survey in the region to balance the bias introduced into prehistoric research by using historic lowland settlement models. This suggested exclusion of historic settlement models from prehistoric research designs and the recommended uplands survey orientation are not supported by the archaeological sites recorded during the 1996 Stage 1 survey of the South Voisey’s Bay Project. Instead, as suggested by McCaffrey et al. for the Seal Lake area, these sites are considered to indicate light prehistoric and early historic occupation in the area, or a tendency during these periods to choose ” … immediate shore-side campsites that would be destroyed by spring floods” (1989:127).

Extrapolations based on the 1996 Stage 1 results and sites known in other areas, together with available Innu land use and occupancy data, allow extensive sections of South Voisey’s Bay Project area to be assessed as comprising zones of high archaeological potential. These culturally sensitive areas are distributed along interconnected lakes and streams flowing through low valleys, with the assessed potential zones occurring for the most part less than 30 m above water level. The exceptions include segments of Innu travel routes crossing saddles at higher elevations.

In contrast to the lower elevations, no historic resources were identified in the upland areas systematically surveyed in 1996 or at any of the potential drill holes at high elevations assessed earlier in the project. Consequently, the overwhelming bulk of the uplands in the project area is considered to be of low or no archaeological potential. Historic interior settlement sites are concentrated in relatively sheltered locations on lakes, ponds, and water courses at low elevations. Use of the barren uplands was limited essentially to travel from one valley to another and to hunting excursions, with various elevated formations serving as vantage points. These activities would have left almost no structural or material remains. A similar pattern is suggested for prehistoric use of the interior uplands.

Recommendations

The main goal of the 1996 Stage 1 Historic Resources Overview Assessment of the South Voisey’s Bay Project was to determine whether historic resources were present in gridded areas of interest. Assessment work in most of these areas involved systematic survey and, in some instances, judgmental sampling of all localities which can reasonably be expected to contain historic resources. This work yielded no evidence of historic resources and, accordingly, no further archaeological research is recommended in any of the surveyed areas of interest.

On the other hand, the proactive component of the survey resulted in the registration of eight new archaeological sites, at least two of which correspond to campsites reported by Innu land use and occupancy data. These results are considered to indicate a significant archaeological potential for the project area in general, and for low elevation zones in particular. The following recommendations are forwarded as preliminary measures for the protection and sustained manmanagement of known and potential historic resources in the South Voisey’s Bay Project area. These measures take into account the heritage concerns of the Innu Nation and the Labrador Inuit related to the conservation of archaeological resources.

Within this context, it is recommended:

- that no mining exploration, development, or other related work be carried out within the vicinity of the archaeological sites recorded during the 1996 Stage 1 survey. In order to assure the protection of these historic resources, it is suggested that no work be allowed within a minimum radius of 50 m from each site and that all personnel involved in such work (e.g., geologists, geophysics teams and drill crews) be explicitly prohibited from visiting any of the sites.

- that the sites recorded in 1996 be identified by aboriginal names, to be determined by the Innu Nation and the Labrador Inuit Association. Place names for the sites determined by the local Innu and Inuit communities will not only acknowledge past land use and occupancy, but could provide important information regarding traditional knowledge about the area. A request for Innu names for the sites has been forwarded to a representative of the Innu Nation. A similar request should be made to the Labrador Inuit Association.

- that GiCn-4 could serve both as an important educational tool and as a focus for in-depth research into Innu land use and occupancy in the area. In order to assess the significance of GiCn-4 in terms of Innu cultural heritage priorities, it is recommended that the proposed field project be centred on the full documentation and thorough interpretation of the site by knowledgeable Innu elders. This visit to the site should include a training component for young Innu interested in cultural heritage research. Following evaluation of the site’s importance, it is recommended that GiCn-4 be systematically subsurface sampled, in order to determine its full extent and history of occupation. It is also recommended that GjCl-1, the second Innu campsite, be examined and interpreted by the elders during their visit to GiCn-4.

- that future Stage 1 assessments engendered by mining exploration and development work in the South Voisey’s Bay Project include a proactive survey component.

- that the recommended proactive surveys be concentrated in areas provisionally assessed as being of high archaeological potential.

Specifically, it is recommended that future Stage 1 Historic Resources Overview Assessments in the South Voisey’s Bay Project emphasize a proactive approach focused explicitly on goal-oriented research. This approach necessarily stresses the intensive survey of zones of high archaeological potential as one of its key elements. In order to be effective, these proactive surveys need to be organized on the basis of regional research designs accommodating the cultural heritage concerns of the Innu Nation and the Labrador Inuit. The central goal of these surveys is to contribute to a better understanding of the culture-history of interior central Labrador and to promote the development of appropriate measures and policies for the sustained management of historic resources in the region.

References Cited

Scott M. and A. Bruce Ryan

1989 – “A Reconnaissance Archaeological Survey of the Kogaluk River Area, Labrador.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s

Fitzhugh, William W.

1972 – “Environmental Archaeology and Cultural Systems in Hamilton Inlet, Labrador.” Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, Number 16, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

1977 – “Indian and Eskimo/Inuit Settlement History in Labrador: An Archaeological View.” In, Our Footprints are Everywhere, Carol Brice-Bennett, ed., Labrador Inuit Association, pp. 1-41.

Leacock, Eleanor

1969 – “The Montagnais-Naskapi Band.” In, Contributions to Anthropology, David Damas, ed. National Museums of Canada Bulletin, 228:1-17, Ottawa.

MacLeod, Donald

1967 – “Field Season Report: 1967.” Archaeological Survey of Canada, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull.

1968 – “Field Season Report: 1968.” Archaeological Survey of Canada, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull.

McAleese, Kevin

1993 – “Labrador Interior Waterways (Kanairiktok River Basin), Phase 2 Report.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s.

McCaffrey, Moira T.

1989 – “Archaeology in Western Labrador.” In, Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1986, J. Callum Thomson and J. Sproull Thomson, eds., Culture and Heritage Division, Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s. pp. 72-113.

McCaffrey, Moira T., Stephen Loring and William W. Fitzhugh

1989 – “An Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Seal Lake Region, Interior Labrador.” In, Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1986, J. Callum Thomson and J. Sproull Thomson, eds., Culture and Heritage Division, Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s. pp. 113-163.

Penney, Gerald

1996 – “Historic Resources Overview Assessment of Drill and Camp Sites in Northern Labrador, 1996.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s.

Pilon, Jean-Luc

1982 – “Le site Neskuteu au Mushuau Nipi (Nouveau-Qué bec): manifestation de la pé riode archaÏque.” Université Laval, Centre d’é tudes nordiques, Collection Nordicana 46, Qué bec.

Robbins, Douglas

1995 – “Preliminary Report on an Historic Resources Overview Impact Assessment in the Area of Kakashipishuneakamats (Pants Lake).” Report submitted to GeoScott Exploration Consultants Inc.

Samson, Gilles

1978 – “Preliminary Cultural Sequence and Paleo-environmental Reconstruction of the Indian House Lake Region, Nouveau-Quebec.” Arctic Anthropology 15(2):186-205.

1981 – “Pré histoire du Mushuau Nipi.” On file, Direction du Nord-du-Qué bec, Ministère de la Culture et Communications, Qué bec.

Tanner, Vaino

1944 – “Outlines of the Geography, Life and Customs of Newfoundland-Labrador.” Acta Geographica Fenniae 8 (1, parts 1, 2), Helsinki.

Taylor, J. Garth

1977 – “Traditional Land Use and Occupancy by the Labrador Inuit.” In, Our Footprints are Everywhere, Carol Brice-Bennett, ed., Labrador Inuit Association. pp. 49-58.

Thomson, J. Callum

1984 – “A Summary of Four Contract Archaeology Projects in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1984.” In, Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1983, J. Sproull Thomson and J. Callum Thomson, eds., Culture and Heritage Division, Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s. pp. 82-97.

1985 – “A Summary of Three Environmental Impact Evaluations in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1984.” In, Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1984, J. Sproull Thomson and J. Callum Thomson, eds., Culture and Heritage Division, Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s. pp. 154-165.