Trevor Bell and M.A.P. Renouf

Introduction

This paper presents the rationale for, and preliminary results of, a test of two models of sea level history at the Port au Choix National Historic Park, on the northwest coast of Newfoundland (Figure 1). Each model provides a different explanatory framework for the known archaeological data, and has different implications for the design of archaeological site surveys. The broader objective of this project is to understand the human prehistory of Port au Choix within the context of palaeo environmental change. The project is an example of the value of integrating sea level history with archaeological survey, and the preliminary results provide an appropriate model for understanding the sea level and human history in other areas on the west coast of Newfoundland.

Figure 1. Port au Choix Peninsula and Gros Morne National Park, northwestern Newfoundland.

The Archaeological Record at Port au Choix

Port au Choix has been occupied by human groups almost continuously for over four thousand years. The earliest evidence of human occupation pertains to the Maritime Archaic Indians, who created a large cemetery which they used from 4400-3300 BP (years before present). Despite extensive site surveys on the Point Riche and Port au Choix Peninsulas from 1984 to 1986 and from 1990 to 1992, the Port au Choix Archaeology Project was unable to locate the Maritime Archaic settlement site that must have complemented the cemetery [1, 2]. Sites pre-dating the cemetery were not found, consistent with the known prehistory of the Island of Newfoundland which has no known sites earlier than 5000 BP [3, 4]. In contrast, Maritime Archaic Indian sites from southern Labrador date as early as 8000 BP, and are well represented after 6000 BP [5, 6].

At Port au Choix, the Maritime Archaic Indians are followed in time by 1500 years of Palaeoeskimo occupation, from 2800 to 1300 BP. Several important Palaeoeskimo sites have been excavated at Port au Choix, including Groswater Palaeoeskimo dating from 2800-1900 BP, and Dorset Palaeoeskimo dating from 1900-1300 BP [7, 2]. As soon as the Palaeoeskimos left Port au Choix, prehistoric Recent Indian groups appeared, staying on a regular or intermittent basis until approximately 800 years ago, at which time the long lineage of aboriginal occupation of Port au Choix appears to end.

Relative Sea Level History

Sea levels fluctuate in response to the growth and decay of continental ice sheets due to changes in ocean volume (glacio-eustasy) and vertical adjustments of the Earth’s crust (glacio-isostasy). Along the margins of formerly glaciated regions mantle material, displaced from beneath the depressed crust under the ice sheet, forms a peripheral forebulge tens of metres in amplitude and several hundred kilometres beyond the ice limit [8, 9, 10]. Following deglaciation, the forebulge collapses by flowing back towards the ice sheet centre. Due to the viscous nature of the mantle, there is a lag effect between melting of the ice sheets and re-establishment of isostatic equilibrium, such that many glaciated regions still experience glacio-isostatic effects 10,000 years after the ice sheets melted.

During the last glaciation (Late Wisconsinan), the southeastern margin of the Laurentide Ice Sheet extended to the Atlantic Ocean across the northern tip of the Northern Peninsula and abutted Newfoundland ice centred on the Long Range Mountains [11].

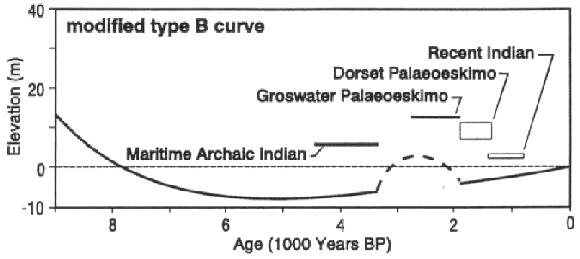

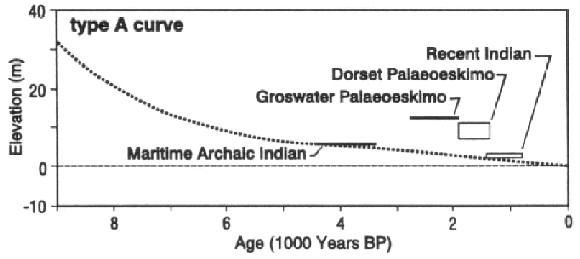

Postglacial relative sea level history on the peninsula is complex resulting from isostatic crustal rebound due to ice unloading and crustal subsidence due to migration and collapse of the forebulge associated with the Laurentide Ice Sheet and, to a lesser extent, local ice caps [9, 10, 12]. Grant [13, 14] presented two models of sea level change for the Port au Choix region based primarily on radiocarbon-dated shells from beach deposits: the first displays a more or less continuously falling sea level to the present for the northern part of the Great Northern Peninsula (type A curve; Figure 2) whereas in the second, sea level falls below its present level by 8000 BP and subsequently rises to the present (type B curve; Figure 2). A brief sea level oscillation above present is postulated between 3500 and 2000 BP (Figure 2), based on the occurrence of a low, fossil sea cliff that lies just above present tide level along the west coast of the peninsula. As an erosional feature the sea cliff cannot be dated directly, but its age may be bracketed by the fact that it is cut into 4000 year old beaches at Port au Choix and is overlapped by 1000 year old beaches farther north. This apparent sea level oscillation may be attributed to a collapsing forebulge moving through the area [14].

Figure 2. Two models of sea level history proposed for the Port au Choix region.

Figure 3. Age-distribution of known prehistoric sites at Port au Choix superimposed on the modified type B sea level curve.

Integrating Archarological and Sea Level Data

The age distribution of known prehistoric sites at Port au Choix, grouped according to their cultural designation, reveals two marked absences in the archaeological record: (i) Maritime Archaic sites dating earlier than 4400 years ago, and (ii) Maritime Archaic habitation site(s) that are contemporaneous with the Maritime Archaic cemetery. Before addressing the question of the environmental/cultural significance of these absences, it is critical to establish a solid baseline of representative sites. Maritime Archaic Indians were marine-oriented and occupied sites within easy access of the sea [15]. The relative position of the sea at the time of occupation, therefore, is a critical factor in directing archaeological site surveys. The models of sea level history presented by Grant [14] warrant further investigation in terms of the age-distribution of known sites above their contemporary sea level and the potential location of “missing” sites in the local archaeological record.

Superimposing documented cultural periods from Port au Choix on the modified type B sea level curve from the Great Northern Peninsula (Figure 3) suggests that Groswater and Dorset Palaeoeskimo sites were located approximately 9-10 m above sea level at the time of occupation, whereas the Maritime Archaic cemetery was at least 14-15 m a.s.l. when it was in use. This would imply that the cemetery was placed on high ground and that any habitation sites would have been located closer to the active beach, and thus today would be at, or below, present sea level. Similarly, any earlier Maritime Archaic sites, from the period 7000-5000 BP, would likely be submerged below present sea level. Comparison of the same site data with the type A sea level curve (Figure 4) reveals no consistent pattern of site elevation above sea level but nevertheless demonstrates that the absences in the local archaeological record are real and may have environmental and/or cultural significance.

Previous archaeological site surveys have relied on the premise that potential Maritime Archaic habitation sites are likely to be found at the same elevation above present sea level as the cemetery. If, however, the modified type B sea level curve can be substantiated through further research, then future surveys would focus on potentially favourable sites close to modern sea level or in the shallow water offshore. On the other hand, we are also aware that a simple type B curve may characterize the sea level history of the Port au Choix region.

Figure 4. Age-distribution of known prehistoric sites at Port au Choix superimposed on the modified type A sea level curve.

Approach and Preliminary Results

We are in the process of testing these models of sea level history, and have completed one of two seasons of fieldwork. We will be relying primarily on the “lake isolation” method, which can detect brief, low amplitude fluctuations in sea level. This method attempts to date boundaries between marine and lacustrine sediments in lakes that have been isolated (or inundated) by changing sea level. These boundaries are identified by litho- and biostratigraphic indicators of salinity changes (e.g., diatoms) in the sediment and dated by the radiocarbon method. Variations in lake salinity over time can be directly attributed to sea level fluctuations relative to the elevation of the lake-basin threshold.

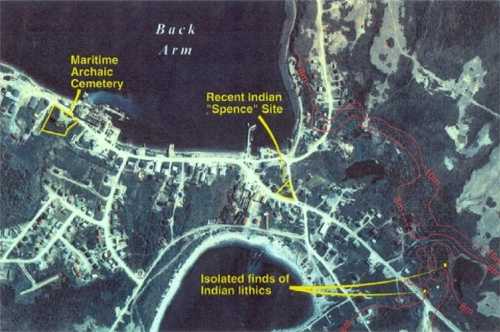

Interviews with local residents about archaeological material directed us to a beach ridge at ~9 m a.s.l., on which only four people have built houses. The cemetery is located on a sandy beach at 6 m a.s.l., which would have been ideal for digging but unsuitable for living. In contrast, the 9 m beach is limestone gravel, which would have provided a better drained surface for setting up a camp or settlement. The 9 m beach is covered by up to 1.5 m of peat and a heavy growth of tuckamore, which would obscure any indication of prehistoric human activity. The possibility that this beach was the site of a Maritime Archaic settlement will be further explored through intensive archaeological testing in 1997. Meanwhile, the local sea level history will be refined using sediment cores from selected ponds and radiocarbon-dated fossils.

Figure 5. Aerial photograph of the central town site of Port au Choix. The ~9 m beach ridge which has strong potential for former Maritime Archaic Indian habitation is broadly outlined by the 8 and 10 m contours. Note the dense tuckamore cover in this area of town. Two of the four houses built on the ridge uncovered Maritime Archaic artifacts.

Acknowledgements: This project is supported by a Special New Research initiatives Grant from the Office of the Vice-President (Research), Memorial University of Newfoundland. Diagrams were drafted by Gary E. McManus, Memorial University of Newfoundland Cartographic Laboratory.

References

- Renouf, M.A.P. 1992. “The 1992 Field Season at the Port au Choix National Historic Park.” Unpublished report on file at Archaeology Division, Canadian Parks Service, Atlantic Region, Halifax.

- Renouf, M.A.P. 1993. “Palaeoeskimo Seal Hunters at Port au Choix, Northwestern Newfoundland.” Newfoundland Studies, 9(2): 185-212.

- Carignan, P. 1975. The Beaches: a Multicomponent Habitation Site in Bonavista Bay. Archaeological Survey of Canada. Mercury Series, 39. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada.

- Tuck, J. A. 1982. “Prehistory in Atlantic Canada since 1975.” Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 6:210-223.

- McGhee, R. J. and Tuck, J. A. 1975. An Archaic Sequence from the Strait of Belle Isle, Labrador. National Museum of Man, Mercury Series, 34. Ottawa.

- Renouf, M.A.P. 1977. “A Late Palaeo-Indian and Early Archaic Sequence in Southern Labrador.” Man in the Northeast, 13:35-44.

- Renouf, M.A.P. 1994. “Two Transitional Sites at Port au Choix, Northwestern Newfoundland.” In Proceedings of Arctic Prehistory: Taylor-Made: Papers in Honour of W.E. Taylor, edited by J-L Pilon and D. Morrison, 165-196. Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- Walcott, R.I. 1970. “Isostatic Response to Loading of the Crust in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 7:716-727.

- Quinlan, G. and Beaumont, C. 1981. “A Comparison of Observed and Theoretical Postglacial Relative Sea Level in Atlantic Canada.” Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 19:1146-1163.

- Quinlan, G. and Beaumont, C. 1982. “The Deglaciation of Atlantic Canada as Reconstructed from the Postglacial Relative Sea Level Record.” Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 19: 2232-2246.

- Grant, D.R. 1989. “Quaternary Geology of the Atlantic Appalachian Region of Canada.” In R.J. Fulton (ed.): Quaternary Geology of Canada and Greenland. Geological Survey of Canada, Geology of Canada no. 1, 391-440.

- Liverman, D.G.E. 1994. “Relative Sea Level History and Isostatic Rebound in Newfoundland, Canada. Boreas, 23: 217-230.

- Grant, D.R. 1992. “Quaternary Geology of the St. Anthony-Blanc Sablon Area, Newfoundland and Quebec.” Geological Survey of Canada, Memoir 427, 60 p.

- Grant, D.R. 1994. “Quaternary Geology of Port Saunders Map Area, Newfoundland.” Geological Survey of Canada, Paper 91-20.

- Tuck, J.A. 1976. Ancient Peoples of Port au Choix, Newfoundland. Social and Economic Studies, 17. Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland.