Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador 1996

Edited by K. Nelmes

An Archaeological Survey of Area 9, Forest Management District 14, Western Newfoundland

F.A.C. Schwarz and L.M. Schwarz

Rationale and Objectives

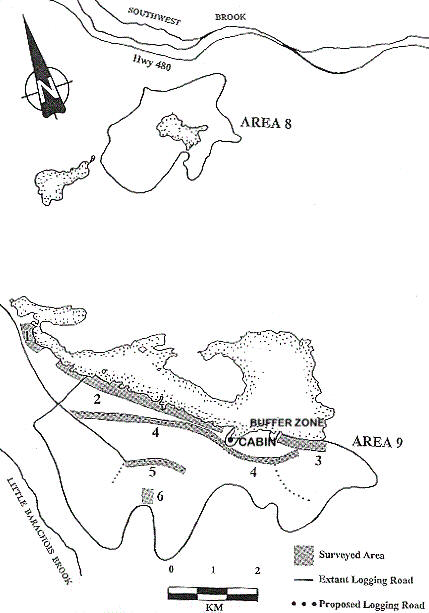

The objective of this assessment was to determine if culturally significant remains existed within the bounds of Area 9 or in such close proximity that they would be affected by imminent logging of the area. Logging is projected to cover most of Area 9, with the exception of two small buffer zones around a few extant cabins. Discussion with the proponent’s silviculture staff, working in Area 8 concurrently with the archaeological project, revealed that the cabins are actually a hunting outfitter’s camp, and that the outfitter had been granted a 300 m buffer zone around his camp by the provincial government, rather than the presently mandated 20 m buffer zone around shorelines. Logging also requires two extensions of the present access road, totalling ca. 8 linear km, in order to provide vehicle access (see Figure 1).

Projected impacts upon any archaeological sites would include logging road construction, logging itself and the damage caused by heavy machinery. Sequelae could include improved accessibility of the area for recreational purposes and increased soil erosion post-harvesting. The proponent estimates the immediate physical impact on any cultural resources in affected areas to go as deep as 30 cm below the present surface.

Figure 1. Logging Area 9, Forestry Management District 14.

Research Design

Area 9 is an irregularly-shaped area of some 13 km2 with 5.5 km of lakeshore frontage. Only a narrow strip of flat land borders the lake, in some areas as narrow as 1 m, with much of the area south of the shoreline being steeply sloping and, therefore, having limited archaeological potential. The eastward extensions of the logging road run along a plateau above the lake. The lakeshore was deemed to have some historic resources potential, and other portions of the area had similar potential.

Area 9 was surveyed in two stages. In the first phase, we focussed on the lakeshore west of the outfitter’s buffer zones and their immediate hinterland (up to 200 m back) and the shorter and most southerly of the eastward extensions of the road. In the second phase, we surveyed the narrows at the western end of the pond, the longer of the two eastward extensions of the logging road, the westward extension of the road and that portion of Area 9 east of the outfitter’s buffer zones.

Since the buffer zones are, by definition, to be protected, the decision was made not to attempt to survey them, especially given the outfitter’s presence on site on July 11. Although these locations lie outside the proposed harvesting area, they are deemed to have high archaeological potential; the cabin location is in the only sheltered embayment on the southern shore of the pond and the other buffer zone is at the mouth of a small stream. In general, prehistoric populations in the interior tended to favour as campsites easily accessible areas near fresh water, often near constrictions in the terrain which would have channelled caribou during their migrations or near constrictions in freshwater lakes where anadromous fish would pool (Schwarz 1984). These same factors often determine the siting of cabins.

Methodology

Since no actual boat-launching area was known to exist in the area by the proponent and the survey area was relatively small, we decided to survey it on foot, a technique which provided maximum coverage of the area to be surveyed but which precluded survey on the northern shore of the pond within the time constraints of the project.

Surface visibility was limited throughout most of the survey areas by extremely heavy forest cover, a mixture of hardwood and softwood forest with dense undergrowth, especially near the lakeshore. Survey along the lakeshore consisted of searching for any area with a reasonable landing area nearby and any flat, dry areas which might have allowed for prehistoric occupation. We found few such areas on the south shore of the pond and our subsurface testing was therefore restricted, although any natural or artificial surface exposures were checked. More shovel-testing was done at the western narrows, even though the terrain close to the lakeshore was boggy.

Survey along the projected logging roads involved a mixture of judgmental survey, as described above, mixed with a program of systematic test-pitting, 20 x 20 cm shovel-tests being excavated at 6-10 m intervals where dry, level, potentially habitable ground was encountered. Near the proposed southernmost fork in the logging roads, test pits were excavated on the nearby height of land.

Related Archaeological Work

Previous archaeological work in Newfoundland has established that prehistoric settlement in the Newfoundland interior was more extensive, at least in some periods, than was once believed. In particular, near-coastal interior waterways, especially lakes and ponds situated within 30 km of the coast have yielded significant evidence of prehistoric settlement. In Western Newfoundland, Thomson (1987) found sites on Portland Pond and Parson’s Brook Pond while Reader located sites on Deer Lake (1994). Penney (1988), and Gilbert and Reynolds (1989) have also found sites well away from the Newfoundland coast, most primarily related to the establishment of Recent Indian late fall/winter seasonal base camps established primarily to hunt caribou. Schwarz (1987 and 1992) also located Recent Indian, Archaic and Dorset sites on Gambo Pond.

Area 9 adjoins a small pond on a tributary of Southwest brook, some 30 km from the estuary of the St. Georges River, and is therefore in a type of setting which would generally be deemed to have high historic resources potential. The unknown factor in southwest Newfoundland is the degree to which prehistoric hunter-gatherers seasonally exploited game along the streams flowing into St. Georges Bay. While recent surveys in St. Georges Bay have apparently yielded little evidence (Penney, personal communication), a multi-component Dorset and Recent Indian site (DdBq-1) was found at the isthmus of the Port au Port Peninsula, near the northern side of St. George’s Bay, some 30 km from the head of the St. Georges estuary (Simpson 1986). Moreover, sites have been located in the St. Georges Bay hinterland (though it is not clear that these sites were seasonally related to DdBq-1). First, a multi-component historic Micmac and prehistoric Recent Indian site was located by Penney on King George IV Lake in the Lloyds River drainage, 25 km south of Area 9 (Penney 1987). Second, and closer to the study area, a substantial secondary deposit of waterworn Dorset artifacts was found by Penney (1980) at Long Pond in the Flat Bay Brook drainage, only 15 km west of Area 9, attesting to the existence (or former existence) of a probably deflated Palaeoeskimo site located unusually deep in the interior, presumably somewhere upstream of the actual find spot.

Previous work had established, then, that prehistoric remains are present in the St. Georges Bay area and its interior hinterland, indicating that Area 9 had at least generic archaeological potential. Prehistoric hunter-gatherers living in the St. Georges Bay area would have had a number of travel route options for seasonally accessing interior resources including: Fishels Brook, Flat Bay Brook, Little Barachois Brook, and Southwest Brook. If Southwest Brook (and specifically its southern tributary) was indeed used as a travel route into the interior, then the pond adjoining Area 9 – the first pond on the brook, conveniently situated approximately one day’s canoe travel from the head of the estuary – would be a natural settlement location. The field assessment was aimed at determining whether this potential had been realized.

The Archaeological Survey

Areas surveyed were generally along linear features such as the shoreline and the proposed logging road extensions, with one series of test pits on a hilltop. Figure 1 shows the areas surveyed, and indicates the numbers assigned to each survey area.

Figure 2. Survey Area 1, View North to the Narrows from the Boat Dock.

Survey Area 1

Lynne Schwarz surveyed the western side of the narrows nearest to the logging road, moving northward from a rough all-terrain vehicle track left by the outfitter, who uses it to access a small boat dock (Figure 2). Although the topography is flat in this area, only a 2-3 m strip adjacent to the shore is dry, the rest being boggy with predominantly black spruce forest cover. Five test pits were excavated within 1-2 m of the shoreline, wherever the growth of mound-forming wild shrubs would permit. None of these tests went more than 6 cm below surface through undifferentiated sand before encountering bedrock. No cultural remains were encountered.

Survey Area 2

Fred and Lynne Schwarz surveyed along the southern edge of the pond from the boat dock along a generally featureless, rockbound shore with little level land (see Figure 3). Two test pits were excavated at one area where there seemed to be sufficient flat land to be habitable, with a stream nearby. Nothing was found in the samples which revealed an 8-12 cm thick humus layer, with an underlying Ae horizon some 10-15 cm thick. Another series of three test pits were excavated at a less promising but level area further east, with similar results. Both of these test areas were west of Area 9’s boundaries. Survey was carried along the shore to a point close to the start of the buffer zone around the cabins.

Figure 3. Survey Area 2, View NNW Across the Pond from the South Shore.

Survey Area 3

Fred Schwarz accessed the strip of shoreline falling within the bounds of Area 9 east of the outfitter’s cabins after survey along the proposed logging road extension. No testable areas were found.

Survey Area 4

The proposed northernmost extension of the logging road runs primarily through fir and spruce-covered boggy ground, offering no testable locations.

Survey Area 5

Accessed via the extant logging road, the proposed location of the road has been clearly flagged by the proponent. Lynne Schwarz shovel-tested every 6-10 m, conditions permitting. This road is slightly higher in elevation than Area 4 and conditions were marginally such as to mandate subsurface testing, even though the predominant tree cover of black spruce and ground cover of spaghnum moss indicated a seasonally waterlogged environment. Test pits generally found 10-15 cm of wettish peat, with an underlying Ae horizon 5-15 cm deep. It should be mentioned that this area was reached by an investigative transect walked along the ridges between the Southwest Brook and Little Barachois Brook drainages.

Survey Area 6

No conclusive indication of the track of the small westward extension of the logging road was found but, according to the topography, this road will fork off the extant road at the base of a height of land some 489 feet above sea level. There were several markings in fluorescent paint on the road at this point, some stakes and two apparent year dates marked on rocks which presumably indicate the harvest year for the parcels of land north and south of the marker, but no flagging in the assumed area of the road which is made impassable by downed timbers. As a hunting lookout, however, the nearby hill, which offers an excellent vantage point over much of the survey area and over much of the pond adjacent to Area 9, had some prehistoric site potential and Lynne Schwarz excavated 4 test pits at its highest point.

Stratigraphy in the test pits was quite different from that encountered in other subsurface tests during the survey, consisting of a shallow layer of dry humus 4-7 cm deep, underlain by an organically-enriched sand over bedrock. In the area tested, only widely-spaced shrubby cover was encountered. No cultural remains were found.

Summary

While no archaeological sites were found during the course of this survey, our survey area in fact excluded an area of moderate historic potential, that of the outfitter’s cabin, and other more obviously habitable areas on the northern lakeshore such as the large peninsula jutting into the lake.

According to the Land Capability Maps (1972) for ungulates, the area surrounding the pond is classified as 4R, indicating that there are moderate limitations to its carrying capacity, primarily caused by poor soil development, but presumably also by the relatively steep topography. More optimal areas for caribou migrations and better ungulate habitat in general include the nearby Lloyds River/Red Indian Lake drainage and the southern shores of Granite Lake and Meelpaeg Lake.

Although salmon runs along Southwest Brook proper have been high in the past (Murray and Harmon 1969), there is little data on whether they make it upstream to the pond adjoining Area 9. A limiting factor to prehistoric use of the area may lie in the navigability of the brook which actually drains into Southwest Brook. Although Southwest Brook itself looks navigable north of Logging Areas 8 and 9, the brooks draining into it are extremely rocky and shallow; salmon might navigate the brook, but canoes would most probably not be able to follow. Located so near to more easily navigable watersheds with higher ungulate carrying capacity (cf. Penney’s Dorset finds on Long Pond), this area could easily have been too marginal to be of any interest to prehistoric populations.

Survey of such regions remains a necessity, though, since, in contradistinction to coastal areas, archaeological research in the Newfoundland interior is still in its infancy and the criteria for determining historic sites potential in the interior in general and in southwestern Newfoundland in particular can only be refined through fieldwork.

References

Environment Canada

1972 – “Land Capability for Wildlife – Ungulates, Red Indian Lake Map Sheet.” Government of Canada publication, Ottawa.

Gilbert W. and K. Reynolds

1989 – “Report of an Archaeological Survey: Come-by-Chance River and Dildo Pond.” Report on file, Historic Resources Division (since renamed Culture and Heritage Division), St. John’s.

Murray, A.R., and T.J. Harmon

1969 – A Preliminary Consideration of the Factors Affecting the Productivity of Newfoundland Streams. Fisheries Research Board of Canada Biological Station, St. John’s.

Penney, G.

1980 – “A Report on an Archaeological Survey of Bay d’Espoir.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.

1987 – “Report on an Archaeological Survey of King George IV Lake.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.

1988 – “An Archaeological Survey of Western Notre Dame Bay and Green Bay.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.

Reader, D.

1994 – “The Deer Lake/Upper Humber River Archaeological Survey 1993.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.

Schwarz, F.

1987 – “On Gambo Pond: A Preliminary Report of an Archaeological Survey of Gambo Pond and Terra Nova Lake, July-August 1987.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.

1992 – “Archaeological Investigations in the Exploits Basin: Report on the 1992 Field Survey.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.

1994 – “Palaeo-Eskimo and Recent Indian Subsistence-Settlement Patterns on the Island of Newfoundland.” Northeast Anthropology 47:55-70.

Simpson, D.

1986 – “Prehistoric Archaeology of the Port au Port Peninsula, Western Newfoundland.” Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s.

Thomson, C.

1987 – “Archaeological Survey of Two Interior Remote Cottage Areas at Parson’s Pond and Portland Creek Pond.” Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.