Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador 1996

Edited by K. Nelmes

An Archaeological Survey of Grand Lake-North West River, Central Labrador, 1996

Lynne M. Schwarz and Frederick A. Schwarz

Introduction and Research Plan

Fieldwork in the North West River-Grand Lake area was undertaken by Black Spruce Heritage Services as part of a broader Historic Resources Overview Assessment of Forest Management Districts 19 and 20, encompassing much of central Labrador. The Overview Assessment involved mapping zones of archaeological potential in central Labrador on a scale of 1:250,000, using, for the most part, existing archaeological and ethnographic data. On the coast, where archaeological research has been relatively extensive, known site distributions served to directly indicate archaeological potential. In the interior, data on aboriginal land use, particularly Innu land use, served as direct indicators of recent and historic sites potential, and as proxy indicators of pre-contact potential as well. The methodology and results of the Overview Assessment are summarized elsewhere (Schwarz 1997); the purpose of this report is to describe the relatively limited fieldwork component, undertaken in June 1996.

As for the field research component, in view of the large project area and the limited time available for field research, it was felt that fieldwork should be focused on a particular area for which prediction of archaeological potential is made difficult by the lack of previous archaeological survey, and an absence of other forms of data on which to base predictions.

Specifically, it was proposed that the most significant gap in our archaeological understanding of the region pertains to the potential for Maritime Archaic settlement at high elevations in interior (formerly inner-bay) regions. This was considered to be a significant gap for the following reasons:

- The existence of Maritime Archaic settlement in such locations has been predicted on the basis of previous studies of settlement patterns in coastal regions of Labrador.

- Despite the theoretical plausibility of these predictions, such sites have never been identified. This is because such sites would be situated at high elevations some distance behind and above the present coastline: Previous coastal surveys have tended to focus on exposed outer-coastal locations, where site visibility is high, while the limited interior surveys have generally focused on low-elevation lake- and river-side locations. Forested high-elevation locations on the margins of the ancient coastline, which are relatively difficult to access, have fallen between the cracks of previous survey efforts, and thus have never been closely examined.

- If such sites exist well above and behind present waterways, then they are likely to be particularly sensitive to forestry activities; they are also less likely than more recent sites to be protected by the maintenance of uncut buffer zones along lake and stream margins.

- The existence and locations of such sites cannot be predicted on the basis of data on present resource distributions, historic, ethnographic, or recent settlement and land-use, or late pre-contact archaeology, since the environmental parameters which would have influenced Maritime Archaic settlement did not obtain in the more recent past.

In addition to the outer coastal portions of Groswater Bay, and the Labrador coast from Groswater Bay to the southern margin of the project area, south of Sandwich Bay, where high elevation Maritime Archaic sites have already been recorded, there are two regions in which deep inner-bay Maritime Archaic sites might be found. Both regions extend a considerable distance inland from the present coastline. One consists of the higher elevations behind the margins of Grand Lake and the present mouths of the Naskaupi, Beaver, and Susan Rivers. The other consists of higher elevations along the lower reaches of the Churchill River Valley. Both regions have been affected by drainage changes associated with the Churchill Falls hydroelectric development. While erosion has accelerated along the Churchill River as a result, water levels in the Naskaupi drainage and Grand Lake appear to have dropped; this latter region was therefore considered to have greater potential for the preservation of Maritime Archaic sites if these in fact exist.

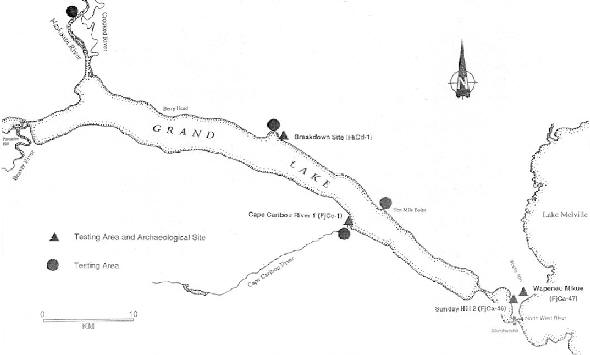

Prior to fieldwork, an examination of air photos of the Grand Lake area indicated that the lakeshore here is generally steeply sloping, with little evidence for level ancient beach terraces. However, level ground was identified at suitable elevations at the following areas (see Figure 1): 1) the long moraine north of the present community of North West River, 2) the southern side of the mouth of the Cape Caribou River, 3) Ten Mile Point, 4) the large unnamed cove midway along the northern shore of Grand Lake, 5) the lower reaches of the Naskaupi River, and 6) Porcupine Hill and the lower reaches of the Beaver and Susan Rivers.

Figure 1. Archaeological Activities in the Grand Lake-North West River Area.

Relationship To Previous Work

Initial Archaeological Research

The basic archaeological sequence for central Labrador was initially developed by William Fitzhugh during the late 1960’s and early 1970’s (Fitzhugh 1972, 1974, 1975, 1977, 1978). This sequence provided the basic culture-historical and culture-processual framework for all subsequent archaeological work in Labrador north of the Strait of Belle Isle, and, since most of the research subsequently undertaken by Fitzhugh and his associates has focused on coastal regions to the north, it remains the definitive sequence for east-central Labrador to this day.

Fitzhugh located and excavated sites in Hamilton Inlet, along a lengthy east-west transect stretching from the coast at Groswater Bay to the interior at North West River. These sites were dated by means of a combination of radiocarbon dating, correlation of artifact styles with those from other regions, and correlation of site elevations with a regional post-glacial uplift curve. Fitzhugh found evidence for significant differences in the occupation histories of Groswater Bay and North West River. Groswater Bay showed evidence for lengthy occupation by a diversity of more or less coastally-adapted Indian, Inuit and Palaeo-Eskimo cultures. North West River, on the other hand, had a briefer sequence composed entirely of Indian occupations, broadly grouped into three periods: Maritime Archaic, Intermediate Indian, and Recent Indian. Some of these exploited coastal resources to some degree, but others seemed restricted to interior fishing and hunting.

The earliest well-defined human occupation in Hamilton Inlet is not actually represented at North West River. These Maritime Archaic sites were identified only at the eastern end of Hamilton Inlet, on the northern shore of Groswater Bay. Hamilton Inlet Maritime Archaic was initially divided into two phases, dated by elevation and radiocarbon assays: the Sandy Cove Complex (6000-4700 BP) and the Rattlers Bight Complex (4000-3800 BP). Fitzhugh has subsequently refined the dating on the Sandy Cove Complex to 5200-4500 BP (Fitzhugh 1978:89). Rattlers Bight retains its original culture-historical position, with the addition of information from the discovery of a cemetery site (Fitzhugh 1978:85) and by the retrospective recognition of “longhouse” structures at the site (Fitzhugh 1984:13). In addition, a third, intrusive, Maritime Archaic occupation, the Black Island Complex, was subsequently defined and dated to 4500-4100 BP (Fitzhugh 1975).

Although Maritime Archaic sites were not identified in the vicinity of North West River, models of Maritime Archaic subsistence-settlement systems include hypothesized inner-bay settlement in the autumn and interior hunting camps in winter. Fitzhugh proposed that undiscovered Maritime Archaic autumn and winter sites might yet be located at high elevations (greater than 100 ft.) north and west of North West River in ancient inner-bay locations along the present drainages of the Churchill River and Naskaupi River/Grand Lake.

The subsequent Intermediate Indian period is best known from sites around the present community of North West River, at the western end of Hamilton Inlet. The earliest occupation recognized at North West River was the Little Lake Component (3600-3200 BP), represented by a small collection of quartz, quartzite and purple chert tools found at a single site, located at 68 ft. a.s.l. The assemblage includes a projectile point similar to late Archaic styles in New England and the Maritimes. The date of the Little Lake Component was derived from the site’s elevation, and from projectile point styles. This is followed by sites of the Brinex (3200-3000 BP) and Charles (3000-2700 BP) complexes, found at elevations of 221-224 m and 13-18 m respectively. Subsequent work on the north-central coast has led Nagle (1978) to collapse these into a single culture-historical unit, the Saunders Complex (3500-2800 BP). Sites of this period are generally characterized by cobble hearths, associated with points, bifaces, endscrapers, and large, well-finished scrapers made from a variety of red and white quartzites, quartz, and colourful pink, tan, purple and red cherts thought to derive from interior sources. The following two Intermediate Indian occupations, the Road and David Michelin components, are poorly defined and, like the Little Lake component, their validity as culture-historical units has yet to be verified. The final Intermediate Indian occupation at North West River is even more perplexing. The North West River Phase, dated to 1800-1400 BP by site elevations of 7-11 m, appears to be well-defined and well-represented, at least at North West River. Large and numerous sites yielded assemblages of bifaces and flake tools manufactured of locally available white-brown quartzite. Sites of this phase are, however, virtually unknown on the north-central coast. The one dated component, from a site near Davis Inlet, suggests that the North West River Phase may follow closely after the Saunders Complex (ca. 2600-1800 BP), and throws further doubt on the culture-historical validity of the Road and David Michelin components.

The Intermediate Indian period is followed by the Recent Indian Point Revenge Complex, which is characterized by circular, oval, and occasionally elongated hearths associated with corner-notched projectile points, bifaces, triangular scrapers and flake tools manufactured almost exclusively from Ramah chalcedony. Point Revenge was originally dated to after 1000 BP. As with the Charles and Brinex complexes, Point Revenge has since been recognized as a widespread culture-historical unit, with numerous sites identified in coastal and interior regions. More recently, work on the north-central coast has led Loring (1989) to define an additional early Recent Indian “Daniel Rattle Complex,” dating ca. 1800-1000 BP.

Sites dating to the protohistoric and early historic period in central Labrador were, and still remain, elusive, but later historic Aboriginal sites were noted by Fitzhugh; historic Inuit sites (the “Ivuktoke Phase”) appear to be restricted to the eastern portions of Hamilton Inlet, while historic lnnu sites (the “Sesacit Phase”) are concentrated around the western end of Lake Melville and the neighbouring river valleys (Fitzhugh 1972:116).

The historic “Settler” period along Grand Lake is, of course, represented by the community at North West River (where the Hudson’s Bay post drew Innu to trade and eventually settle), and by a small, early 20th century settlement on the Naskaupi.

Subsequent Work at Grand Lake-North West River

The most significant archaeological work in the area was that undertaken by Fitzhugh in and around the present community of North West River in the late 1960s, described above. Fitzhugh also conducted limited and largely unreported survey work on Grand Lake at the same time and, in addition to this, minor work has subsequently been undertaken in the vicinity of the present community.

It is clear from his monograph that Fitzhugh did survey Grand Lake and the lower Naskaupi River, at least briefly. However, references to this work are vague and at times obscure (some additional details are given in McCaffrey et al. 1989). Fitzhugh recorded a major historic-period Innu campsite on the Naskaupi, opposite the mouth of the Red Wine River, and in a later publication (presumably referring to the same work), he indicates Innu sites at Ten Mile Point and the mouth of the Beaver and Susan rivers (Fitzhugh 1977: Map 5). In addition, Conrad (1969) refers to a lithic stray find at Berry Head, again presumably recovered during Fitzhugh’s work in the area.

Nearer North West River itself, Thomson (1984) conducted an Historic Resources Impact Assessment of the proposed Mokami Trail in 1984. The proposed route for this hiking trail ran 50 km from North West River to the foot of Mokami Mountain on the Sebaskachu River. Thomson surveyed the trail head and the lower Sebaskachu, locating historic Innu campsites in the latter area, but determined that the remainder of the route ran at elevations of 30-50 m above the 3500 BP shoreline, and therefore had very low archaeological potential.

In 1987, flakes and artifacts of tan quartzite and Ramah chalcedony were found by a local resident near the aggregate quarry on Sunday Hill, north of North West River. Despite the high elevation (45 m a.s.l.) these appeared to pertain to an Intermediate Indian occupation, perhaps of the North West River Phase. Thomson (1987) and Penney (1988) both visited the site and recovered similar additional material, mostly debitage.

Definition of the Research Issues

Although the subsistence-settlement patterns for these areas are clearly incompletely defined, it is nevertheless the case that a sizeable database is at hand with which to predict the frequency and locational attributes of Intermediate Indian, Recent Indian, and Innu sites in the project area.

The most problematic exception is the Maritime Archaic period, for which the nature and extent of settlement in the project area remains a mystery. Fitzhugh originally suggested that Maritime Archaic settlements in former inner bay regions would be difficult to locate because of their high elevation and interior locations, which would render them relatively inaccessible, and because of their low archaeological visibility owing to heavy forest cover (Fitzhugh 1975:118). Perhaps these factors continue to explain the lack of evidence for such early sites. Essentially, such sites, if they exist, would be inaccessible and inconspicuous, and their locations would be hard to predict; the limited survey that has been conducted in these areas has not been done in a way that could lead to the recovery of such remains.

Thus, the original and prevailing model of Maritime Archaic subsistence and settlement in central Labrador predicts that autumn/winter base camps should be situated at high elevations (ca. 100 ft. a.s.l.) in ancient inner bay locations now located north of North West River and in the present lower Churchill and lower Naskaupi/Grand Lake drainages. This prediction had never been adequately tested; consequently the potential for, and the nature and extent of, Maritime Archaic remains in this important part of the project area remained unclear.

The fieldwork component of the Historic Resources Overview Assessment of Forest Management Districts 19 and 20 was aimed at testing this prediction. The proposed fieldwork was not intended to represent a comprehensive test of this prediction, owing to time constraints. However, it did represent the first deliberate test, and was targeted at certain locations which air photo examination indicate as suitable habitable terraces at the right elevations.

Methodology

Locations were initially identified on air photos which complied with the criteria already discussed. All areas inspected were subjected to intensive pedestrian survey in a search for Maritime Archaic remains, involving surface inspection and examination of natural exposures such as eroding terrace fronts and tree falls, in search of artifact scatters and cobble hearths and alignments. Inspection of surface exposures is the major traditional archaeological survey method in Labrador, though its suitability in forested regions is suspect.

Conditions on the terraces varied between open lichen woodland, heavy coniferous forest, and exposed, burnt-over terraces as at Cape Caribou. In most places, there were very few surficial exposures and, in most cases, the terraces themselves were not easily visible from the lake. Intensive, systematic test-pitting was usually necessary once dry, level, habitable terraces were located. Testing involved excavation of 20 x 20 cm shovel tests to depths of 20-30 cm with square-bladed shovels, at intervals of 6-12 m, as conditions permitted. Despite the time of year, deep forest cover sometimes resulted in semi-frozen soil which could be excavated, but only at a rather slower rate than would otherwise have been the case.

Sites encountered were tested to ascertain cultural affiliation, but this was not conclusive in the case of the sites found on Sunday Hill and along the Mokami Trail (see below), since no actual diagnostic artifacts were located. Test pit locations on identified sites were mapped, along with any surface-visible features.

Although the Labrador interior is frost-free between 10 June and 14 September (Fitzhugh 1977) we encountered some partially-frozen soils in areas where heavy tree cover insulated the ground.

All sites were mapped, photographed and plotted onto 1:50,000 scale topographic maps.

The Environmental Setting

Grand Lake is a NW-SE trending lake located near Goose Bay, Central Labrador. Part of the Naskaupi River system, debouching into Little Lake and thence into Lake Melville, Grand Lake is a freshwater lake fed by the Naskaupi, Susan, Beaver, and Cape Caribou rivers. Topographically, Grand Lake is generally steep-sided, but with low deltaic deposits to the west, at the mouths of the Naskaupi and Beaver/Susan Rivers, and a broad coastal plain to the east, along the shore of Lake Melville. The modern communities of North West River and Sheshatshit are located here. Tree cover consists primarily of Boreal Forest Species, including white spruce (Picea glauca), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), black spruce (Picea mariana), eastern larch (Lari laricina) with lichens and mosses as ground cover. Where the Grand Lake fire has destroyed the forest canopy, some birch (Betula papyrifera) and aspen (Populus tremuloides) are recolonizing the area. Although Labrador has extensive bogs, the slopes of Grand Lake are generally well-drained but species such as Labrador tea (Ledum groenlandicum) are found on disturbed soils, such as the margins of the Mokami Trail.

Local food resources for people today include caribou (Rangifer tarandus), a variety of species of freshwater fish, waterfowl, and small game such as ptarmigan and spruce grouse. In the pre-contact period, when relative sea level was higher, seals were probably also more widely available in the North West River-Grand Lake area.

Fieldwork on Grand Lake

Air photos of the Grand Lake area indicated that its lakeshore is generally steeply-sloping, with little evidence for level ancient beach terraces. However, level terraces were identified at suitable elevations in the following areas (Figure 1):

- Location 1: The long moraine north of the present community of North West River;

- Location 2: The southern side of the mouth of the Cape Caribou River;

- Location 3: Ten Mile Point;

- Location 4: The large unnamed cove midway along the northern shore of Grand Lake;

- Location 5: The lower reaches of the Naskaupi River; and

- Location 6: Porcupine Hill and the lower reaches of the Beaver and Susan Rivers.

Location 1: Sunday Hill-Birchy Hill

Sunday Hill is located on the northern boundary of the community of North West River. Gravel mining operations have removed a significant portion of the hill, with a municipal park protecting the hill’s southern flank. In 1987 the local resident who discovered the Sunday Hill site reported finding lithic artifacts from the margins of the quarry area, and subsequent visits by Thomson (1987) and Penney (1988) identified a severely disturbed site of probable Intermediate Indian and Recent Indian date. Thomson (1987) also attempted to investigate a proposed quarry location on Birchy Hill. In 1996, our brief surface inspection in the Sunday Hill area on June 16 encompassed the park, the western rim of the gravel pit, and a path leading directly from the open pit northwards; survey also extended from the Sunday Hill area north along the Mokami Trail to the flanks of Birchy Hill.

Sunday Hill 2 (FiCa-46)

During the course of our survey of the park and the gravel quarry on June 16, we located two possible cultural loci (Figure 2) which are probably related to this same Sunday Hill site complex, and which we designated Sunday Hill 2. The two loci are approximately 120 m apart.

Figure 2. View North Across Sunday Hill 2 (FjCa-46), with Locus 2 in Foreground, Locus 1 in Background on Right.

Locus 1 is situated along a narrow side road which leads northward from the pit and eventually dips down to a bog along the margins of Little Lake. Surface finds at Locus 1 consisted of three tiny pieces of quartz shatter and one probable quartz flake. Locus 2, to the south, is situated on a disturbed road surface near the still undisturbed western rim of the gravel pit operation. Surface finds on several low terrace-like steps along this road (Figure 2) included one large, flat quartz flake and one cortical flake of pink quartzite. Since these all represent potentially local lithic materials, and since all were found on disturbed surfaces in an active quarry, their cultural status is not definitely established. However, several of the pieces do appear deliberately flaked, and the proximity of a known site justifies assigning a Borden number to these finds. No firm cultural affiliation could be ascribed to the site.

Wapineu Mikue Site (FjCa-47)

As mentioned previously, Thomson (1984, 1985) surveyed the Mokami Trail in 1984. His map and descriptions indicate that he conducted some subsurface testing along the trail’s southernmost 2 km at elevations between 20-25 m a.s.l., then tested a promising terrace on the Sebaskachu River, with no results. There is, however, no indication of the number or precise locations of test pits in either of the Mokami Trail reports.

On June 16, survey northwards from the trail’s southernmost terminus found no testable locations until we came to a steep terrace frontage on the southern margin of Birchy Hill, 3 km NNE of North West River and 1 km W of Lake Melville, some 17 m above sea level. At the edge of this terrace, ten quartzite flakes, two chert flakes and some fire-broken rock were exposed in the sandy fan created by use of the trail, an erosional area which is now some 14 m at its widest extremity. This unusually large erosional area probably results from people accelerating snowmobiles and/or all-terrain vehicles to negotiate the steep slope, and perhaps also using the change in elevation as a turnaround spot. Three test pits were excavated to the east of the trail in lichen woodland along and behind the terrace edge, with negative results. Six test pits were excavated to the southwest, only one of which yielded a flake. This, along with intensive investigations of the blowouts at the edge of the plateau, suggest that in situ deposits remain at least a short distance west of the trail cut. The site is unlikely to exceed 450 m2 in area, about half of it probably destroyed.

Though diagnostic artifacts are lacking, the site has been tentatively ascribed to the Intermediate Indian Brinex Phase (ca. 3000-3200 BP), based upon lithic materials (a quartzite-dominated debitage collection). The elevation (17 m) is perhaps more consistent with a Charles Complex date (3000-2700 BP), but in any case, an Intermediate Indian cultural affiliation of some sort seems certain. Further excavation would be needed to refine this attribution.

The site’s location indicates that the North West River site complex may be more extensive than previously thought and that similar locations in the area (terrace margins now situated some distance inland) have high archaeological potential. The site was named for the winter partridge wing found hung by a string in a tree near the site, amid other signs of recent Innu harvesting activities.

Location 2: Cape Caribou River

Survey and shovel testing was conducted on a terrace 10 m above the lake and adjacent to the river mouth and also on a 15-25 m terrace to the south, an area burnt over during the Grand Lake fire and still not re-forested. The resulting lack of tree cover meant that the ground was ice-free in most units.

Testing along the 10 m terrace in 6 test pits revealed a strata of grey clay ranging from 2-35 cm in depth underlain by 10 cm of grey sand which, in turn, is underlain by orange substrate. Testing on the 15-25 m terrace at 5 m intervals, we found a patchy burnt and humus layer ranging from 5-7 cm, underlain by a leached layer of 4-12 cm over orange substrate in the 14 test pits excavated. Some test pits had a buried humus layer located some 4-7 cm below the surface. All the test pits on these two terraces were devoid of artifacts.

Cape Caribou River 1 (FjCc-1)

As we were leaving the area after testing on the terrace, we noted that the point of land on the north side of the mouth of the Cape Caribou River might have been a desirable campsite for modern hunters. Subsequent survey on June 15 found a Recent Innu campsite in a clearing in the alders, its remains consisting of tent pegs, fire-cracked rock, a hearth, one raised hearth (presumably indicating the former location of the tent), a wooden table with firewood stacked beneath it and a rack of propped tent poles. A trail leads away from the site to the southwest. Given the low elevation of the site, on a sandbar, the site could not have been first occupied more than 25 years ago, when flooding of the Smallwood Reservoir lowered the level of Grand Lake, making such sites habitable. In fact, most of the cultural features observed likely date to within the last year or two. It should be noted that the encampment would not have been easily visible from the lake.

Location 3: Ten Mile Point

Commencing on June 12, survey began by boat out of the community of North West River. At the first test area selected, just south of Ten Mile Point on the south bank of Grand Lake, an area around the cabins was initially surveyed by visual surface inspection, and then a narrow 50 m terrace fragment upslope and northwest of the brook was surveyed and tested. Fourteen test pits were excavated in closed-crown spruce-fir forest near the crest of the ridge. Unfortunately, some 15-25 cm below the surface, the humus was full of ice crystals, but was still penetrable; this was underlain by fully frozen soil 3-5 cm down into the leached stratum. Excavation through to the Bf horizon thus proceeded very slowly. Small lenses of charcoal were noted throughout the top 2 cm of the Bf horizon. All the units were culturally sterile. At the landing spot in the nearby cove and behind the beach 4 test pits were excavated, revealing undifferentiated sand under the humus layer close to the present beach, with grey sand underlain by red sand under a 10 cm deep humus layer in the woods.

Survey along the beach and on the alder-covered point to the southeast was unproductive.

Location 4

Here we surveyed and shovel-tested the three moderately well-defined stepped terraces above and behind the cove. All terraces were covered in closed-crown spruce-fir forest, with occasional lichen patches, though trees were noticeably more widely-spaced, and lichen cover more extensive on the highest terrace in the series.

On the 30 m terrace 5 test pits were excavated with duff 12-15 cm thick, underlain by some charcoal flecks and then a leached layer 2-25 cm thick, then subsoil. Test pits on the 35 m terrace came upon bedrock or large boulders just under the surface in the 6 units excavated. On the 40-45 m terrace, 6 test pits came upon 17-20 cm of duff, then 5-10 cm of Ae horizon, underlain by a 5-10 cm thick subsoil. In most units the substrate consisted of large cobbles. All the units were culturally sterile.

The Breakdown Site (FkCd-1)

Survey along the shoreline of the cove at this location 15 km northwest of Ten Mile Point, found a stone hearth under alder cover on a point of land which defines the eastern side of the cove, close to a small brook. Given the alder tree cover and the low elevation of the site above Lake Melville the age of this site is estimated at 10-25 years old, postdating the flooding associated with the Smallwood Reservoir. There were some cut timbers in association with the hearth.

Location 5: The Lower Naskaupi River

During our survey of the mouth of the Lower Naskaupi, we passed an Innu family encamped at the mouth of Crooked River, continuing a pattern of intensive use of this area which dates back into the historic period and most probably, the pre-contact era. A trading post was once located near the river mouth but there are no firm data on its precise location or condition. Although work on the Lower Naskaupi was planned for the three 100 ft. terraces visible in air photos on both sides of the lower Naskaupi, we concentrated our attention on one broad terrace located inside a deep meander some 7 km upstream from the rivermouth. The 100 ft. terrace here rises behind a lower riverfront terrace 2-3 m above river level, indicating that the higher terrace has not been cut by river action in the recent past. It has been subject to gullying, however, and proved to be bisected by a very broad, deep gully approximately at its midpoint. Some 75 test pits were excavated in lichen woodland along this broad and long terrace at 6-10 m intervals over the course of two days. Most of the pits east of the stream gully revealed a similar stratigraphy of 10-15 cm of moss, underlain by 3 cm of humus, with a dark leached layer of 0.5-5 cm overlying a lighter leached layer of 3-5 cm. West of the gully, the stratigraphy was comparable, except for the appearance of charcoal in a strata above the light grey leached level. There were ice crystals in some units, especially in the leached horizon, but not enough to seriously impede testing. All units were culturally sterile.

Location 6: Lower Beaver and Susan Rivers

Due to time constraints, this locale was not tested, the survey strategy focusing instead on the Lower Naskaupi, known to be a choice campsite during the historic period.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Fieldwork on Grand Lake was undertaken as part of a broader Historic Resources Overview Assessment of Forestry Districts 19 and 20 in central Labrador. The Overview Assessment was for the most part intended to be document-based, predicting archaeological potential across this vast area on the basis of existing archaeological, ethnographic, environmental and land-use data. The limited fieldwork component was undertaken with the very precise objective of testing the hypothesis that high-elevation interior marine terraces in the region, in former inner-coastal settings, had potential for Maritime Archaic sites. This hypothesis, suggested primarily on the basis of archaeological data, could not otherwise be verified using existing literature.

Examination of air photos led to the identification of six locations in the Grand Lake area with terraces or terrace fragments at suitable elevations. During fieldwork in June of 1996, five of these six locations were accessed and tested as planned. No definite Maritime Archaic sites were identified in the locations investigated. At this level, the survey achieved the stated objectives, and must be considered a success. But can we say that the potential for Maritime Archaic sites on high-elevation terraces in formerly inner-coastal locations is low? In retrospect, it must be questioned whether the fieldwork constituted a very complete test of the hypothesis.

The problem lies in the nature and preservation of marine terraces in the Grand Lake Area. Following the 1996 fieldwork, it appears now that apart from the vicinity of North West River itself, extensive and well-preserved marine terraces are generally lacking in this area. Probable (though not well-defined) marine terraces do exist on the shores of Grand Lake, and several were tested. However, these generally proved to be fragmentary. Extensive terraces do exist at high elevations along the lower Naskaupi, but these now appear to be river-cut, almost certainly in the post-Archaic period. This is probably true too of the terraces seen in air photos of the Porcupine Hill area. Such terraces have potential for later pre-contact riverine sites, but Maritime Archaic sites at these elevations have likely been destroyed by river action. In short, the potential for marine Maritime Archaic sites in the Lake Melville hinterland remains moot.

There are several areas apart from Grand Lake in which this hypothesis may be tested, however, and future work on this question should probably focus on these. One such area is the 100 ft. terrace at the eastern edge of the town of Goose Bay. This high, steep-fronted terrace has probably been cut somewhat by river action as well, and presently, the road to the ferry terminal runs just behind the edge of this terrace. As a result, archaeological remains here may not be well-preserved. However, it is possible that former Archaic occupation here could be identified, and certainly this terrace is easily accessible, with no logistical difficulties. A second location, and one with considerable potential, is the coastal plain south of Carter Basin, where marine, riverine, and former-rivermouth terraces are abundant and well-preserved.

While the question of Maritime Archaic settlement in western Lake Melville remains unanswered, the 1996 fieldwork did lead to the discovery and recording of four new sites. Two are situated on Grand Lake, both near the present lake level, and dating to within the last generation, and two are in the vicinity of North West River, both at higher elevations, and both dating to the pre-contact period. The nature and distribution of these sites does have useful and important implications for the future management of archaeological resources in the region. Particularly significant is the Intermediate Indian Wapeneu Mikue site, situated several kilometres north of North West River, and about 1 km from the present lakeshore. Several valuable lessons can be learned from this damaged Intermediate Indian site.

First, and most exciting, the presence of this site indicates that the North West River site complex may be considerably larger than was previously imagined. Additional loci, if only small outliers, may yet be discovered along the terraces north of the present community. This is particularly important, since expansion and infilling of the community of North West River appears to have significantly depleted the archaeological resources of this site complex, at least as it was initially defined. It is perhaps even more important now to ensure that the status and distribution of this site complex is assessed in detail prior to any further expansion of the community.

Second, and more broadly, the site serves to underline the archaeological potential of ancient marine terraces situated in low-lying coastal plain areas, often a considerable distance from the present shoreline. This is not exactly a revelation; such landforms could always be expected to yield archaeological sites. However, they are often neglected in archaeological research and assessment, in favour of similar terraces situated closer to the shore. Certainly, terraces in coastal plain settings are less accessible from the water, but it can never be assumed that their potential is lower. The results of recent work in Voisey’s Bay (Labrèche, Schwarz and Hood 1997) also serve to illustrate this point.

References

Conrad, G.W.

1969 – “The Lake Melville Project 1968: A Preliminary Report on the Archaeology of the Central Coast of Labrador.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.

Fitzhugh, W.W.

1972 – Environmental Archaeology and Cultural Systems in Hamilton Inlet, Labrador. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology 16, Washington D.C.

1974 – “Hound Pond 4: A Charles Complex Site in Groswater Bay, Labrador.” Man in the Northeast 7:87-103.

1975 – “A Maritime Archaic Sequence from Hamilton Inlet, Labrador.” Arctic Anthropology 12(2):117-138.

1977 – “Indian and Eskimo/Indian Settlement History in Labrador: An Archaeological View,” in C. Brice-Bennett (ed.) Our Footprints are Everywhere, pp. 1-41. Labrador Inuit Association, Nain.

1978 – “Maritime Archaic Cultures of the Central and Northern Labrador Coast.” Arctic Anthropology 15(2):61-95.

Labrèche, Y., F. Schwarz, and B. Hood

1997 – “Historic Resources Technical Data Report for the Baseline Environmental Assessment of Voisey’s Bay.” Report submitted to Voisey’s Bay Nickel Company, St. John’s.

Loring, S.

1989 – “Tikkoatokak (HdCl-1): A Late Prehistoric Indian Site near Nain,” in J. Sproull Thomson and C.Thomson (eds.), Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador 1986. Annual Report 7, pp. 52-71. Historic Resources Division, Department of Municipal and Provincial Affairs, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s.

McCaffrey, M.T., S. Loring and W. Fitzhugh

1989 – “An Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Seal Lake Region, Interior Labrador,” in J. Sproull Thomson and C. Thomson (eds.), Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador 1986. Annual Report 7, pp. 114-163. Historic Resources Division, Department of Municipal and Provincial Affairs, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s.

Nagle, C.

1978 – “Indian Occupations of the Intermediate Period on the Central Labrador Coast: A Preliminary Synthesis.” Arctic Anthropology 15 (2): 119-145.

Penney,G.

1988 – “Draft Report: Archaeological Survey of Sunday Hill, Labrador.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.

Schwarz, F.

1997 – “An Historic Resources Overview Assessment of Forest Management Districts 19 and 20, South-Central Labrador.” Report prepared for Department of Natural Resources, Forest Management Division, Corner Brook.

Thomson, C.

1984 – “Historic Resources Assessment of the Mokami Mountain Trail.” Report on file at Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.

1987 – “Archaeological Investigations at North West River, Labrador.” Report on file, Culture and Heritage Division, St. John’s.