Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador 1997

Edited by K. Nelmes

Archaeological Surveys Between the Nain and Hebron Regions, Northern Labrador, 1997

Bryan C. Hood

Introduction

This report describes archaeological surveys undertaken between the Nain and Hebron regions of northern Labrador in July 1997. The context of the fieldwork was a combination of research and participation in a hunting trip with my Inuit companions. Consequently, the locations investigated as well as the duration and intensity of the surveys were determined partly by archaeological objectives and partly by circumstances.

There were two central and one secondary archaeological objectives behind the summer’s activities:

- Investigation of Maritime Archaic/pre-Dorset social boundary relations through surveys in the inner portion of Hebron Fjord (previously unknown archaeologically) and Napartok Bay (only briefly surveyed by the Smithsonian). Surveys in these two areas would help complete the north coast surveys between Nain and Hebron and might provide new settlement pattern data to clarify the spatial relationships between the Maritime Archaic and pre-Dorset, specifically, the nature of possible territoriality (Fitzhugh 1984).

- Recording Inuit grave sites. This objective would contribute to expanding a grave site inventory which is a component of the LIA land claims process (Hood 1997).

- The secondary objective was the standard registration of sites of all cultural affiliations.

Site Descriptions

In this section I provide descriptions of each of the newly registered sites from the summer’s fieldwork. I begin with the Nain region and proceed north through Okak, Napartok Bay and Hebron.

Nain Region:

Gang Island

“Gang Island” should perhaps be pluralized, since it actually consists of two adjacent islands. The area does not seem to have been surveyed to any great extent, since only one other site was known previously.

Gang Island-2 (HeCh-17)

The site was located on a small islet just off the south side of the westernmost of these islands. It consisted of a single find of a Late Dorset stemmed/notched endblade of Ramah chert in a small gravel pocket on the highest (8-9 m asl) and most exposed point on the southeastern projection of the islet. No additional tools, flakes or traces of structures were noted, although it was a very brief inspection. This would be an excellent lookout place for uttok-ing in the spring (hunting seals basking beside their breathing holes). Indeed, I believe I was near this area in 1994 on such an uttok-ing expedition.

Although this stray find seems rather minor, it has some small significance in that there is very little evidence for Late Dorset occupation in the Nain region. Currently, I know of only one Late Dorset site on Central Island, slightly to the south of Gang Islands (Fitzhugh 1981:36). The site consisted of two small mid-passage structures, one of which was radiocarbon dated to 685 ± 60 BP (SI-4828, Kaplan 1983:484).

David Island (Kilialuk)

David Island is a large island near the extreme northeastern edge of the Nain archipelago. In 1995 a survey on the southeastern tip of the island revealed historic Inuit summer camps and at least one, possibly two, Maritime Archaic pit houses (Hood 1995). Observation from a distance indicated that the Eastern Harbour area might be productive of prehistoric sites. Proximity to the sîna (ice edge) suggested a potential for Dorset winter sites, parallel to those on adjacent Jonathan Island (Fitzhugh, site record forms). We surveyed a promising area at the head of Eastern Harbour, but failed to find any significant Dorset occupation.

David Island-4 to 8 and 11 were located on a rocky peninsula at the head of Eastern Harbour. More precisely, the sites mostly lay in a series of gravel pockets and small beach terraces which sloped down towards a narrow inlet on the south side of the peninsula. David Island-9 and 10 were located just west of the isthmus connecting the peninsula with the island mass.

David Island-4 (HeCg-14)

Positioned at 17 m asl, the site consisted of a few Ramah chert flakes spread over an area of ca. 10 m2. An incomplete sidescraper of Ramah chert (probably Dorset) was surface collected.

David Island-5 (HeCg-15)

Situated beside a bedrock rise at 21 m asl, this locality consisted of a few gray Mugford chert and green slate flakes spread over an area of ca. 10 m2. It is likely a pre-Dorset site.

David Island-6 (HeCg-16)

Stray find of a probable pre-Dorset adze/celt preform of green slate at an elevation of 14 m asl.

David Island-7 (HeCg-17)

Inuit tent ring.

David Island-8 (HeCg-18)

Two Inuit graves, one cache and a marker stone.

David Island-9 (HeCg-19)

Three Inuit tent rings.

David Island-10 (HeCg-20)

Early Maritime Archaic site consisting of quartz flakes, a hearth and unidentified boulder structures.

David Island-11 (HeCg-21)

Located at the summit of the peninsula, the site included 5 pinnacles and one Inuit grave.

Okak Region:

Iglusuaktalialuk Island

Several sites were registered previously on the eastern side of the island by Steven Cox (1977). Our lunch stop on the southwestern corner of the island permitted only a brief survey of a small area and resulted in the registration of two new sites.

Iglusuaktalialuk-9 (HhCk-11)

The site was located in a gently sloping area south of a stream, in a grassy spot just east of a small rocky point. There were over 20 recent Inuit tent rings and several outdoor hearths. This is a well known summer camp.

Iglusuaktalialuk-10 (HhCk-12)

The site was situated ca. 70 m northeast of Iglusuaktalialuk-9 in a series of sandy blow-outs at 6.5-7.0 m asl. Flakes of Ramah chert, as well as one red chert flake occur over an area of ca. 10 by 15 m. The cultural affiliation is uncertain, but the elevation suggests Middle-Late Dorset.

Kikkektak Island

Part of Kikkektak Island was surveyed previously by Steven Cox (1977:246-247), who registered a possible Dorset site. Our stop was strictly motivated by caribou hunting concerns. Two sites were noticed on the northeast tip of the island, near a small point protected by two rocky islets and shoals. Their presence was reported by one of our crew on his return to the boat, but time did not permit a proper investigation.

Okak Island West-1 (HjCm-6)

During a visit to an Inuit fishing camp at Siugak River, we were told there is a recent/historic Inuit site on the west side of Okak Island, on a point near Branson’s Pond. Apparently there are sod houses and “60 to 70” graves. The site was not visited by us, so the precise position and contents are unconfirmed. Neither Taylor’s (1974:103) nor Taylor and Taylor’s (1977:80) maps of late 18th century or early 19th century Inuit settlement in the Okak area indicate a site at this location.

Kikkektak Island-2 (HjCm-7)

Several Inuit graves.

Kikkektak Island-3 (HjCm-8)

Flake scatter, from which examples of grey Mugford chert and red-brown chert were collected. This is probably a pre-Dorset site and a reinvestigation seems warranted.

Brierly Island

Seven sites were recorded in Brierly Island in 1977 during the Torngat project. We set up an overnight tent camp on the south side of the island. Approaching darkness did not permit anything other than a quick walk-over of the western end of the island, so there was no time to record meaningful details.

Brierly Island West-5 (HkCl-19)

In a boulder field overlooking a previously registered pre-Dorset site (Brierly Island West-1 HkCl-10) were two caches (or a grave and cache). On an east-west terrace to the east were four or five scattered rock clusters, either collapsed cairns (for a caribou fence?) or hearths. Cultural affiliation is unknown, but could be either Maritime Archaic or Inuit.

Brierly Island West-6 (HkCl-20)

At this location there were four rectangular rock alignments, two large, two small, which might be Christian graves.

Napartok Bay Region

Napartok Bay is one of the few portions of the north coast which has never been subjected to a systematic archaeological survey. It seems to be a place which one passes by on the way to more promising archaeology in Hebron or Okak, or a place which one passes with regret because of a compelling need to navigate Cape Mugford while the weather is favourable.

Napartok constitutes the present northern limit of trees in Labrador, although dense stands of shrubs occur further north in Hebron Fjord and Saglek Bay (Elliot and Short 1979). During the period of overlap between the Maritime Archaic and pre-Dorset the tree line seems to have been situated near its present location. Sites such as Nulliak Cove, north of Hebron, indicate that the Maritime Archaic people were capable of living, at least seasonally, north of the tree line, but apparently not north of the shrub-tundra zone (Fitzhugh and Lamb 1985:363). Nonetheless, Napartok may have been attractive to partially forest-dependent Maritime Archaic groups as well as to wood-searching pre-Dorset.

Historically, Napartok was used as a wood collecting area by Inuit from Hebron (e.g., Periodical Accounts 1837:219), but it also had a resident Inuit population. In 1773 Jens Haven reported three Inuit settlements with a total of 140 persons (Taylor 1974:11).

Napartok lies just around the corner from the Mugford chert sources (Gramly 1978, Lazenby 1980), so for that reason alone considerable pre-Dorset activity would be expected here. There are also soapstone deposits on Soapstone Island at the mouth of the bay, which might have been used by the Maritime Archaic (raw material for plummets), Dorset or Inuit (Nagle 1984:116).

Animal resource availability in Napartok can be summarized following Brice-Bennett (1977). The inner parts of the bay have been used by Inuit for spring-summer-fall fishing camps for char and salmon. Spring to fall camps are also found in the outer portions of the Bay. Shark Gut Harbour was used frequently for fall harp sealing by Inuit from Okak (Brice-Bennett 1977:185). In the open water season, harbour seals concentrate in Shark Gut Harbour as well as the west side of Finger Hill Island, while most of the inner parts of the bay and the passage between Soapstone Island and the mainland are good for winter hunting of ringed seals through their breathing holes. Bearded seals are found around Finger Island. Walrus were available between Soapstone Island and the mainland. A polar bear denning area is found on the north tip of Soapstone Island and polar bears are frequently encountered between Cape Mugford and Nanuktut Island. Caribou are present in coastal areas during the summer and interior herds can be accessed in the winter. Black bears are also available.

Smithsonian field parties registered a few sites in the outer portion of Napartok in 1980, while Stephen Loring recorded a site in 1990. Two sites were recorded on Soapstone Island (IaCu-4, Inuit; IaCu-5, pre-Dorset), while four sites were recorded on the mainland across from Soapstone Island (IaCo-1, pre-Dorset and Inuit; IaCn-1, Dorset; IaCn-2 & 3, Dorset). Two sites were recorded mid-way up the north side of the bay (HlCo-1, Inuit and Late Dorset; HlCo-2, Maritime Archaic and pre-Dorset). Kaplan (1983:549) notes a total of eight Inuit sod houses at Napartok Bay-1 (HlCo-1) on the north side of the bay. The variations in house forms probably represent several different occupation periods, including communal houses likely dating to the 18th century.

Although we planned to undertake a fairly systematic survey of the bay, engine problems required that we return to Nain without unnecessary delay. We were only able to spend a couple of hours in the Finger Point area.

Finger Point

Finger Point is a prominent projection on the south side of Napartok Bay, slightly inside the entrance to the bay through Sunday Run. We anchored in the lee of the point, on the southern side. The tip of the point is steep rock, but about 1.2 km to the southwest is an area with gravel beaches, the most prominent of which lies at 19 m, with a steep erosion face that drops down to the modern beach. The terrace is bisected by a deep stream channel. Three sites were recorded on top of the terrace and one near the modern beach. One of our crew made a brief reconnaissance on the north side of the point, reporting the presence of Inuit graves and possible Dorset flake scatters, but it was not possible to record these properly.

Finger Point-1 (HlCo-3)

This site was located near the modern beach front, in a low grassy area bordered on the south by an outcrop of fragmented rusty rocks and on the west by the 19 m terrace. It consisted of an undetermined number of recent and historic Inuit tent rings.

Finger Point-2 (HlCo-4)

On top of the 19 m terrace, and overlooking the tent rings near the modern beach, was a single Inuit communal sod house, presumably dating to the late 18th to early 19th century. It had a very well-defined structure and was excavated into the gravel beach. Rectangular in form, it measured 8.6 m along the back wall, 6.0 m from the back to front walls, was roughly 1 m deep and had an entrance passage 4 m long, 1.1 m wide. Sleeping platforms were present on the back and side walls, the rear platform extending 1.2 m out from the back wall. Boulders littered the floor area and a small whale rib fragment was observed on the floor, underneath some rocks and in front of the entrance passage. There was little cultural accumulation on the floor and there was no obvious external midden, so a short occupation span seems likely. One flake of grey Mugford chert was observed in the house wall. On the gravel ridge which slopes down to the rocky point southeast of the site we observed a drilled soapstone object and a tiny metal harpoon point (recent). The soapstone implement, which was not collected, may be related to the communal house occupation.

Finger Point-3 (HlCo-5)

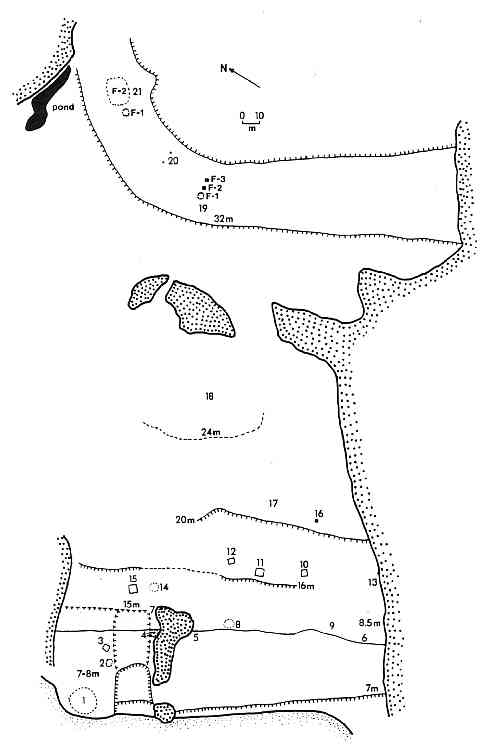

Finger Point-3 was located on the prominent 19 m gravel-cobble terrace. In fact, it extended southwards along the terrace for a distance of ca. 150 m, right up to where the terrace is bisected by a deep stream gully. The terrace front was marked by an accumulation of boulders and cobbles which extended ca. 20 m back from the terrace edge. The remainder of the terrace, extending another 20-30 m back towards a hill to the west, was composed of a partially deflated gravel/cobble matrix. The site itself consisted of 20 features, most of which were located in the boulder field and within 10-15 m of the terrace front. The features were fairly evenly distributed along the terrace, spaced out roughly 10 m apart. Three sparse scatters of Ramah chert flakes were also noted (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Figure 1. Finger Point-3 (HlCo-5), Sketch Map of Feature Distribution.

Figure 2. Finger Point-3 (HlCo-5), Site Overview Towards SW.

There were few clear indicators of cultural affiliation or chronology at this site. The conical pits and rectangular structures are most likely Maritime Archaic (cf. Fitzhugh 1984), but it is not certain that all the other boulder structures and the Ramah chert flake scatters are also Maritime Archaic. Some of the boulder rings are so well preserved that one might suspect a more recent date, perhaps related to the Inuit communal house at Finger Point-2. The function of the features is unclear as well. Some of them are probably storage pits, at least one might be a burial, while some of the boulder ring/pit features are about the right size for small hunting blinds or shelters. The site is clearly in need of more intensive investigation and more detailed documentation of the boulder features. Test pitting is warranted in the vegetated area behind the boulder field, given the presence of overgrown rectangular structures (Features 2 & 20).

If most of these features are Maritime Archaic, then there may be groups of associated rectangular structures and cache pits such as those at the eastern end of the terrace (Features 1 to 5 & 20), possibly in the middle (structure, Feature 18 and pits, Features 6 to 9) and perhaps at the western end of the terrace (tent rings 16 & 17, rings/pits Features 12 to 15). It is interesting to notice that in each cluster the pits occur in groups of four or five. Of course, the presence of additional structures under the vegetation would modify this picture considerably.

Figure 3. Finger Point-3 (HlCo-5), Feature 12, Boulder Ring/Pit, View to SW.

Finger Point-4 (HlCo-6)

This site was located on the same 19 m terrace as Finger Point-3, but on the south side of the stream gully. Four features were identified, all within ca. 30 m of the corner created by the intersection of the marine and brook erosion faces.

Feature 1 was a pre-Dorset mid-passage structure, measuring ca. 3 m in diameter and 2.5 m along the midpassage. The southern lobe of the tent ring seemed to have been mostly destroyed, but the north side was formed by an unusual 60 cm wide ring of tightly packed cobbles. The mid-passage was ca. 60 cm wide and was constructed of small rounded cobbles. Several flat slabs off-centre to the seaward side of the structure indicated a collapsed hearth box. Only a few Mugford chert flakes were observed inside the structure. A grey Mugford chert microblade lay 3 m to the northeast near the brook terrace edge.

Feature 2 lay ca. 20 m south of the mid-passage structure, close to the terrace edge. It consisted of an oval arrangement of loosely clustered boulders, 1.9 m in diameter, associated with a few Ramah chert flakes. This might be a Maritime Archaic burial or cache.

Feature 3 was located ca. 10 m further back on the terrace behind Feature 2. There were several overgrown rocks pertaining to a possible Paleoeskimo structure and one flake of green radiolarian chert (originating in western Newfoundland) was collected. I suspect this is a late pre-Dorset or Groswater component.

Feature 4 lay 10 m back from Feature 1. It consisted of a few overgrown rocks, possibly part of a tent structure.

Hebron Fjord Region

Hebron is a long fjord which extends ca. 50 km inland. In 1830 the Moravians established a mission in the outer fjord area, which was inhabited until the community was closed in 1959. Ecologically speaking, Hebron has much greater resource potential than Napartok (summarized from Brice-Bennett 1977). The fjord is rich in ringed seals, while walrus and bearded seals are available north and east of Kingmirtok Island at the mouth of the fjord. White (beluga) whales were common and bowhead whales were once hunted by Inuit (Taylor 1988). Polar bears frequent the outer coastal area. Spring through fall fishing camps were established in various parts of the fjord, including inner fjord areas such as Freytag Inlet. The inner portions of Hebron are very close to the wintering areas of the caribou herds and large numbers of the animals come out to the coast during the summer. The substantial black bear population may have colonized the area relatively recently. Besides animal resources, there are also soapstone outcrops in Hebron, with documented sources near the abandoned settlement, Cape Nuvotannak, Johannes Point (Nagle 1984, Kaplan 1983), and probably other undocumented localities as well (Fitzhugh, personal communication).

The most prominent archaeological site in the fjord is Hebron-1 (IbCp-17), which consists of the standing remains of the Moravian mission, Inuit sod houses and traces of Maritime Archaic, pre-Dorset and Middle Dorset activity. The site was tested by Kaplan (1983:555-561) during the Torngat Project and by Loring in 1990. Other important sites are Johannes Point-1 and 2 (IbCq- 1, 2), located about 5 km southwest of Hebron-1; these were tested by Kaplan (1983:576-595). Johannes Point-1 consists of Inuit sod houses plus Thule and pre-Dorset components, while Johannes Point-2 contains lnuit, Maritime Archaic, pre-Dorset and Dorset material. Ten sites have been recorded at Grubb Point on the south side of the fjord, across from the Hebron settlement. These sites include Inuit, pre-Dorset and Dorset components. Four sites have been recorded along the mid- to inner portion of the north shore of Hebron. These include Inuit, Thule, pre-Dorset, Groswater, Dorset and possibly Maritime Archaic material.

Bordering Hebron Fjord are several localities with important pre-Dorset and Maritime Archaic sites. On the south side of Hebron is Harp Peninsula/Isthmus, which is home to a significant concentration of pre-Dorset activity. North of Hebron there are pre-Dorset and Maritime Archaic sites at Jerusalem Harbour and the major late Maritime Archaic site of Nulliak Cove (Fitzhugh 1984).

Previous archaeological research in Hebron Fjord has been concentrated in the outer fjord zone. During the Smithsonian’s 1977-78 Torngat Project, parts of the north side of the fjord were visited as far in as ca. 20 km, but subsequent work in the 1980s was focussed at Harp Isthmus and further north in the Jerusalem Harbour and Nulliak areas (Fitzhugh 1984). In 1990, Stephen Loring excavated Inuit house structures and middens at the Hebron settlement. Given this outer coast bias, our goal was to survey selected portions of the deep inner fjord region. As recounted in the narrative, we were partially successful in this endeavour, but ended up exacerbating the coastal bias during our stay at the abandoned Hebron settlement.

Inner Hebron

All the sites discussed here lie within the fjord arm in which an abandoned provincial wildlife cabin is located. This area is an excellent fishing location in late summer, when the char move upriver and into the lake further up the tunnel valley which penetrates deep into the interior. The valley is an important travel route for caribou, which abound here in the summer and fall. Black bears den in the eroded sandy bluffs of remnant glacial-fluvial delta deposits near the entrance to the valley.

A long point, which we named Nuvotanàluk, extends into the fjord at the junction of this inlet and the southwestern arm of the fjord. During the winter, strong currents off the point maintain cracks in the ice where ringed seals may congregate. Uttoks can also be had here in the spring. This may explain the density of Middle Dorset settlement on the point, including a winter house (Nuvotanàluk-4).

Surveys were conducted at low elevations from the wildlife cabin to the mouth of the river; time did not permit investigation of the high bluffs backing the more recent coastal plain. No sites were found in this area. A sandy point on the north side of the inlet ca. 1.3 km east of the cabin, named by us Siugakuluk, was visited by boat. Three sites were recorded there. Another short boat-assisted visit was made to a series of low terraces on the south side of the inlet opposite the cabin. No sites were observed there and the irregular marshy terrain did not appear to be of high potential for settlement. We then shifted our attention to Nuvotanàluk, walking most of the point from the high terraces on the southwest (2.5 km from the tip) to just short of the steep rocky tip. Five sites were recorded here, although we probably missed a number of the small Ramah chert flake scatters which are nestled in gravel patches among the rock outcrops.

Siugakuluk-1 (IaCt-1)

Six recent Inuit tent rings and excavated pits were located near the present shoreline on the western side of the point’s tip. The site has been used by a number of families.

Siugakuluk-2 (IaCt-2)

This site was located on the western side of the point, on a sand/gravel beach at 12 m asl, facing west towards the head of the inlet and sheltered from the strong easterly winds that scour the higher, more visible terrace. The cultural material lay about 10 m back from the terrace edge and covered an area of ca. 25 by 10 m. Besides a flake scatter (mostly Mugford chert) there was a pre-Dorset structure 4.5 by 3.5 m in size, with its long axis oriented parallel to the terrace front. There were several head-sized perimeter rocks, possibly a central hearth and some flat slabs. A small triangular endblade (black chert) was surface collected adjacent to the structural rocks, while a thin slightly shouldered biface base of Ramah chert was collected 3 m to the northeast. Observed near the structure, but not collected, were a knife/biface base (grey Mugford chert), a couple of small stemmed arrow points (black chert), a possible burin fragment and a sidescraper. The most surprising find was made 4 m west of the structure: the basal fragment of a side-notched point of Cod Island chert. This is of Intermediate Indian Saunders Complex affiliation. Also found near the side-notched point was a fragment of a slightly convex-based biface of black chert, which may also be Intermediate Indian.

Siugakuluk-3 (IaCt-3)

The last locality at the point was situated on the highest sand-gravel terrace overlooking Siugakuluk-2 (no elevation was taken, but it was probably well over 30 m). Two oval boulder cairns lay ca. 30 m apart on the sloping terrace surface. Each cairn was ca. 2.0 by 1.5 m in size and the lowest rocks were partly embedded in the gravel. No lithics were associated with the cairns, although the inspection was rather hasty. Cultural affiliation is uncertain, but Maritime Archaic is possible.

Nuvotanàluk-1 (IaCs-2)

This site was located on a northwest-facing gravel beach terrace ca. 2.2 km southwest of the tip of the point (Figure 4). It consisted of five localities representing different occupation periods. Each locality (L) will be described in turn.

Figure 4. Nuvotanàluk-1 (IaCs-2), Site Overview, Towards W.

L-1 lay at 12 m asl on the partially deflated uppermost portion of the beach, backed by a bare bedrock knoll. It consisted of a ca. 90 m by 15 m linear scatter of Ramah chert flakes which ran parallel to the beach and the knoll. The flake scatter was not very dense, although there were a few large (ca. 10 cm long) chunks of Ramah chert. Although the linear distribution resembled the Maritime Archaic longhouse pattern (Fitzhugh 1984), there were no structural components aside from a single rock cluster resembling a hearth.

Very few tools were visible on the surface of L-1. Two probable Maritime Archaic flake points were collected, one broken medially but with a distinct shoulder for a stem, the other crudely retouched on the lateral edges, possibly unfinished. The cultural picture was complicated by finds of a pre-Dorset microblade (grey Mugford chert) and two probable Dorset implements, an unfinished side-notched biface and a preform for a tip-fluted endblade. There was sufficient in situ deposit towards the rear of the terrace such that there is some potential for excavation, although few tools are likely to be recovered.

L-2, 3 and 4 lay on the lowest part of the terrace at 11 m asl. L-2 consisted of two or three rocks, possibly structural remnants, associated with a flake scatter ca. 3 m in diameter with grey Mugford chert, slate, black chert and a bit of Ramah chert. L-3 lay 8 m east of L-2 and consisted of a circular tent ring with a cluster of flat slabs in the middle, probably a collapsed box hearth. Lithic materials included flakes of gray Mugford chert, black chert and Ramah chert. Both L-2 and L-3 are pre-Dorset components.

L-4 was 2 m east of L-3 and consisted of a D-shaped tent ring of head-sized boulders with a U-shaped external hearth. This is probably a 19th century Inuit feature (Kaplan 1983:246).

L-5 was located on the edge of the bedrock knoll, on the southeastern corner of the terrace. The locality consisted of a single Inuit grave with a well constructed chamber of large boulders and a huge flat slab placed on top. A few rib bones, a pelvis fragment and a tibia were visible. The grave appeared to have been opened and looted. A few Ramah chert flakes lay beside the feature.

Nuvotanàluk-2 (IaCs-3)

A Ramah chert flake scatter; a Dorset sidescraper was surface collected.

Nuvotanàluk-3 (IaCs-4)

The site was located on an exposed gravel terrace at 19 m asl. It consisted of a Ramah chert lithic scatter. A few Middle Dorset tools were collected: a triangular endblade (straight based, basally thinned, but not tip-fluted), a tip-fluting spall and a crystal quartz microblade.

Nuvotanàluk-4 (IaCs-5)

This Middle Dorset sod house site was located on a small rock ledge at 12 m asl. The structure was nestled into a rock cleft which provided a settlement area of only ca. 10 by 10 m. The house itself consisted of a 6 by 6 m patch of thick grass with several large rock slabs embedded in the sediment beneath. Ramah chert flakes and tools were eroding out of the edge of the grass patch and had tumbled down the steep embankment. Given the steep slope around the feature it would appear that the debris was cast out of the house and slid downslope, with no midden formation. Dorset implements collected from the eroding edge of the site included: a tip-fluted endblade (flat base, basally-thinned), an endscraper, microblade fragments, a large biface tip of black chert (possibly pre-Dorset?) and a nephrite flake. There were several small Ramah chert flake scatters along the rock outcrops southwest of Nuvotanàluk-4 which were not registered as sites. Overall, there appears to be considerable Middle Dorset activity in the Nuvotanàluk area, much of it probably related to the sod house settlement.

Nuvotanàluk-5 (IaCs-6)

This site was situated towards the eastern side of the point. It consisted of five Inuit graves spaced 30-50 m apart, all of large boulder construction. Two were located in a grassy area near the east side of the point, the others on a bedrock knoll. No construction details were recorded.

Outer Hebron

The surveys in outer Hebron Fjord were concentrated in four areas; Kingmirtok Island at the mouth of the fjord, Kangerdluarsuksoak Inlet, Jerusalem Harbour and the small bay in which the abandoned Hebron settlement was located. All three sites on Kingmirtok were located on the southeastern corner of the island, overlooking the narrow passage between the island and Harp Peninsula. Our brief stop did not permit more than a cursory look, so the descriptions presented below are very superficial. Clearly, though, this portion of the island has high potential for sites of most time periods/cultures and inspection of the prominent gravel terrace just north of our survey area would surely be very profitable. The investigations at Kangerdluarsuksoak Inlet involved a walk-over survey of a pass between the Inlet and Hebron Fjord, ca. 2.8 km south of Grubb Point. The one site at Jerusalem Harbour was the result of a chance encounter on a hunting trip; a proper survey was impossible. Finally, our lengthy stay at the Hebron settlement permitted a fairly comprehensive survey of the surrounding area.

Kingmirtok Island-1 (IbCo-1)

Lay near the present shoreline, recent Inuit tent rings.

Kingmirtok Island-2 (IbCo-2)

In a gravel pocket, slightly higher than Kingmirtok-1 (ca. 8-10 m). A Ramah chert flake scatter covered an area of 30 by 10 m. No tools were observed, but this probably represents a Dorset occupation.

Kingmirtok Island-3 (IbCo-3)

We barely scratched the surface of this large site on a cobble beach. Historic Inuit tent rings and other boulder features were observed, but not recorded in detail. A bone kakkivak was found in one of the boulder features, but was not collected. One of the boulder features was a sub-rectangular rock ring, 2.0 by 1.8 m in size, with three courses of rocks on one side. One metre to the east of the latter feature was a 1 by 1 m cluster of flat slabs and a few Ramah chert flakes. Remnants of an iron stove were also found on the beach. There are evidently historic Inuit and Dorset components here, and it seems likely that there are also Thule features (possibly the rectangular feature?).

Kangerdluarsuksoak Pass-1 (IaCp-18)

Recent Inuit tent rings and caches.

Jerusalem Harbour-2 (IbCp-28)

This site, on the east side of Jerusalem Harbour, was visited briefly by one of our crew during a hunting trip. He reported a Ramah chert concentration and surface collected a Ramah chert stemmed point fragment (missing stem). It is likely of late Maritime Archaic affiliation.

Hebron North-1 (IbCp-29)

Situated 1 km north of the Hebron settlement, the site consisted of one Inuit grave placed on top of a rock outcrop. The feature was 2 by 1.3 m in size and oriented NW-SE. It seemed undisturbed, although no skeletal elements were visible. There may have been a small cache at the eastern end of the grave.

Hebron North-2 (IbCp-30)

This large site was located at the head of the Hebron settlement bay. It extended over several raised beach terraces from about 7 m asl to 32 m asl. Ramah chert flakes occurred sporadically over an area estimated at ca. 350-400 m N-S and 200 m E-W. The highest beach ridge provides an excellent view north to Jerusalem Harbour, and the site vicinity was probably a good place to intercept caribou moving between Jerusalem Harbour and Hebron.

Fairly distinct beach terraces were visible at 7 m, 16 m, 20 m and 32 m (note that these elevations might be a bit inaccurate because of measurement errors over a large horizontal distance). These terraces and their associated features and lithic scatters were sketch mapped (Figure 5); a total of 22 localities were identified. Despite the large size of the site, very few tools were observed on the surface, thus dating of the various beach levels was problematic.

Figure 5. Hebron North-2 (IbCp-30), Sketch Map.

Hebron North-3 (IbCp-31)

Historic Inuit site containing ca. 6 circular tent rings, external hearths and caches and two graves. Grave 1 was of large boulder construction, measuring 2.9 by 1.8 by 0.9 m and oriented E-W. It was disturbed and a femur was visible. Grave 2 was 3 m west of G-1, 2.5 by 1.2 by 0.7 m in size, oriented E-W. It was also disturbed, with long bones and a cranial fragment visible. A piece of beige European ballast flint had been placed in the grave (post burial), supplemented by a crewmember’s 1997 offering of two .22 calibre bullets.

Hebron North-4 (IbCp-32)

Located in a gently sloping beach pass, bordered on three sides by rock outcrops. L-1, at 10 m asl, contained two or three recent Inuit tent rings associated with Ramah chert flakes. L-2, at 14 m asl and ca. 30 m from the L-1 tent ring in the centre of the beach pass, consisted of a series of eroded dry ponds with the remnants of a tent ring and a fair amount of Ramah chert flakes. Surface collected here were: a biface tip of black chert (probably pre-Dorset), three Ramah chert microblade fragments (Dorset) and a small “flake” of soapstone.

Hebron-3 (IbCp-35)

Located 0.6 km north of the Hebron settlement. Three historic Inuit tent rings.

Hebron-4 (IbCp-36)

Situated 0.35 km north of the Hebron settlement. The site lay at 8 m asl in a small sand-gravel blow-out and caribou trail on the south side of a cleft through which a small stream flowed. Only a few Ramah chert flakes and a couple of possible microblade fragments were observed in an area of ca. 10 by 10 m.

Hebron-5 (IbCp-37)

This site consisted of three Inuit graves, up slope (east) of a pond which lay in a low pass between a mountain and a point, 0.55 km north of the Hebron settlement. The first grave was in a rock cleft 10 m from the pond, while the other two lay on a bedrock outcrop, 10 m southeast of the first.

Grave 1 was built inside a rock cleft, which constituted two walls of the grave. The chamber was disturbed, ca. 1 by 1 m in size, oriented N-S. The only visible skeletal element was an ulna. Some bone artifacts were present, but overgrown by moss. The only identifiable item was a bone kayak paddle tip.

Graves 2 and 3 were built end to end alongside a bedrock outcrop, oriented N-S, for a total grave size of 3.3 by 1 m. Grave 2 contained most of the individual’s skeletal elements, although the bones were not in their correct anatomical order (the leg bones had been gathered together in a pile at one end of the grave). The individual was an adult. Grave 3 was mostly overgrown with moss, but a tibia and fibula were visible. Both graves appeared to be relatively undisturbed.

Hebron-6 (IbCp-38)

Two pinnacles located on a point, 120 m east of the Hebron-5 graves. The features were placed on sloping bedrock, ca. 15 m apart. P-1 (lowest) was an upright slab (1.0 by 0.25 by 0.1 m) supported by additional slabs. The upright slab was oriented NW-SE. P-2 was a slab (60 by 14 by 10 cm) wedged into a rock cleft and oriented E-W. Together, these features formed a line pointing towards the Hebron-5 graves.

Hebron-7 (IbCp-39)

One Inuit grave, ca. 65 m east of the Hebron-6 pinnacles and near the extreme tip of the point. The disturbed grave chamber was rectangular, 1.7 by 1.2 m, with neatly placed flat slabs on top. It was oriented N-S. The skeletal material was overgrown with moss, but a skull fragment and a long bone fragment were visible.

Hebron-8 (IbCp-40)

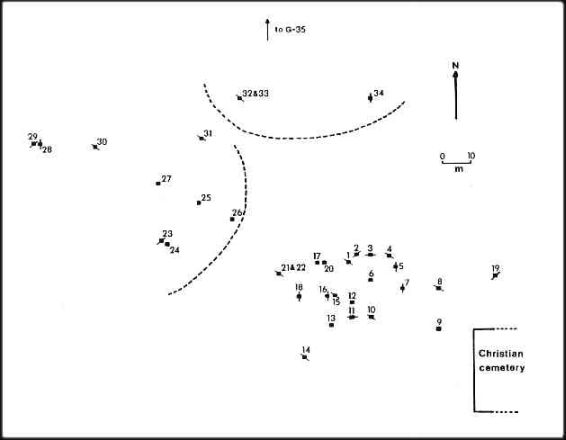

This site was a large Inuit grave field located among a series of rock outcrops over an area extending from ca. 25-300 m northwest of the Hebron settlement’s Christian cemetery. A total of 35 graves were recorded, although a few may have been missed and some have likely been destroyed by later activity. Hebron-8 is the largest documented Inuit grave site in Labrador, besides the Rose Island material from Saglek Bay (cf. Hood 1997, Way 1978).

The graves occurred in roughly three groups (Figure 6). Group I (total=22) lay closest to the Christian cemetery (within 140 m). Group 2 (total=9) lay on a slightly higher outcrop ca. 180-240 m northwest of the cemetery. Group 3 consisted of 3 graves placed on an E-W trending outcrop ca. 180 m NNW of the cemetery.

Figure 6. Hebron-8 (IbCp-40), Sketch Map of Grave Distribution.

Of the total 35 graves, 12 were classified as almost completely destroyed, while most of the others exhibited some form of disturbance. It seems likely that this grave field was the source of at least some of Jewell Sornberger’s 1897 skeletal collection from Hebron, which is now curated at the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Of the 24 graves for which cardinal orientation could be recorded (magnetic, not adjusted for declination), 12 (50.0%) were oriented NW-SE, 4 (16.7%) NE-SW, 6 (25.0%) N-S, and 2 (8.3%) E-W. In other words, a total of 22 (91.7%) were oriented more or less N-S, only 2 (8.3%) E-W. This can be compared to the overall NS-EW orientation of the Christian graveyard, with E-W orientation of the individual Christian graves.

Despite the degree of disturbance, there is some discernable variation in the form and construction of the graves. Five graves (1, 10, 11, 16, 34) are larger and sometimes better formed than the others; one of these (G-11) had whale bone inside, while another (G-34) had an associated external cache. One “average” sized grave (G-23) was associated with an external cache. These distinctive graves might be indicative of status distinctions.

Hebron-9 (IbCp-41)

One Inuit grave, located on a high rock outcrop on the spine of a point south of the Hebron settlement. The grave was large, 2.4 by 1.0 m, built against the bedrock and oriented N-S. A skull lay on the north end of the grave (facing the fjord) and a few long bones were visible. A disturbed external grave cache (square, 80 by 80 cm) lay 3 m north of the grave.

Hebron-10 (IbCp-42)

Four or five large graves were located on gravel beaches on the southwestern portion of the second largest of the Dog Islands, east of the sod houses at the southern end of the Hebron settlement. These features were observed from the mainland, not visited directly.

Hebron-11 (IbCp-43)

This site was located 130 m north of the Christian cemetery, 200 m west of the modern shore and 80 m southwest of a stream valley with a pond. The site lay in a pass between a low bedrock outcrop and a hill. Ramah chert flakes were found within and adjacent to a caribou trail. Seven small test pits were excavated between the caribou trail and an indentation in the hill to the west. Only four pits contained cultural material, which consisted solely of Ramah chert flakes: TP-1= 23 flakes, TP-2= 4 flakes, TP-3= 43 flakes, TP-7=7 flakes. A few flakes were burned, but no trace of charcoal was observed in the test pits. Four or five of the flakes might be the proximal ends of microblades, but the fragments were so small that no definitive identification was possible.

Conclusions

The results of the survey were somewhat disappointing in relation to the original objectives, but this was obviously a consequence of mechanical problems with our boat engine. Nonetheless, some of the newly recorded sites were of special interest and have some bearing on broader problems in Labrador culture-history.

The most important find was probably the Dorset sod house at Nuvotanàluk-4, deep inside Hebron fjord. This site has interesting implications for our understanding of Dorset settlement patterns. Existing interpretations of Dorset settlement patterns emphasize a strongly outer coast orientation of the Dorset culture (Spiess 1978, Cox and Spiess 1980). This model seems to apply well in the intensively surveyed Nain region, where there are extremely few Dorset sites in the inner island-inner bay zones. Thomson (1986:28) draws similar conclusions for the fairly well-surveyed Saglek Bay region. On the other hand, a significant Dorset occupation is present deep inside Nachvak Fjord, at the Nachvak Village site (IgCx-2), where Dorset material is superimposed by an Inuit sod house and midden complex (Kaplan 1983:678-703). The deep inner fjord location of this settlement is linked to the presence of a polynya at the junction of the fjord and its offshoot, Tallek Arm.

It is highly likely that the inner fjord location of the sod house at Nuvotanàluk-4 is related to ecological factors similar to those present in Nachvak: the presence of a polynya, or at least regular ice cracks. These two examples suggest that existing Dorset settlement models must be modified to account for such regional variations in subsistence conditions. Additionally, one might question whether sufficient attention has been paid to surveying inner bay areas elsewhere in northern Labrador.

As far as our original problem of Maritime Archaic/pre-Dorset boundary relations is concerned, we were unable to acquire much new material that would contribute to clarifying the issue. The traces of pre-Dorset, and possibly Maritime Archaic, identified in the inner reaches of Hebron Fjord might be taken to indicate overlapping use of the inner fjord rather than territoriality. On the other hand, we only surveyed one of the three inner fjord arms. The outer coast surveys in the vicinity of the Hebron settlement failed to produce much evidence of either late Maritime Archaic or pre-Dorset. This might be taken as a reinforcement of previous impressions of spatial concentrations of late Maritime Archaic activity in the Nulliak-Jerusalem Harbour area and pre-Dorset in the Harp Isthmus area, with a “No-Man’s Land” in between. However, significant components of either or both cultures might lie hidden beneath the Inuit occupations at the Hebron Settlement, or they may yet be found in unsurveyed areas at Cape Nuvotannak or Kingmirtok Island.

Finally, an unexpected result of the surveys was the identification of Intermediate Indian material at Siugakuluk-2 in inner Hebron. A single possible Intermediate Indian site (no diagnostic tools were found) was previously recorded at Grubb Point-1 (IaCp-5) in outer Hebron (Nagle 1978:137-139). Although the context of the Siugakuluk find is problematic, since it is associated with a pre-Dorset component, it nevertheless tends to confirm some degree of Intermediate Indian activity in the Hebron region. This activity might prove to be an important factor in explaining the relative paucity of late pre-Dorset in the Nain to Hebron areas.

References Cited

Brice-Bennett, Carol

1977 – “Land Use in the Nain and Hopedale Regions,” in Our Footprints are Everywhere: Inuit Land Use and Occupancy in Labrador. Labrador Inuit Association, Nain.

Cox, Steven

1977 – “Prehistoric Settlement and Culture Change at Okak, Labrador”. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, Cambridge.

Cox, Steven, and Arthur Spiess

1980 – “Dorset Settlement and Subsistence in Northern Labrador.” Arctic 33:659-669.

Elliot, Deborah L. and Susan K. Short

1979 “The Northern Limit of Trees in Labrador: A Discussion.” Arctic 32:201-206.

Fitzhugh, William

1981 – “Smithsonian Archaeological Surveys, Central and Northern Labrador, 1980,” in Archaeology in Newfoundland & Labrador 1980, Jane Sproull Thomson and Bernard Ransom, eds., pp. 26-47. Historic Resources Division, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s.

1984 – “Residence Pattern Development in the Labrador Maritime Archaic: Longhouse Models and 1983 Surveys,” in Archaeology in Newfoundland & Labrador 1983, Jane Sproull Thomson and Callum Thomson, eds., pp. 6-47. Historic Resources Division, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s.

Fitzhugh, William, and Henry Lamb

1985 – “Vegetation History and Culture Change in Labrador Prehistory.” Arctic and Alpine Research 17:357-370.

Gramly, Richard Michael

1978 – “Lithic Source Areas in Northern Labrador.” Arctic Anthropology 15(2):36-47.

Hood, Bryan

1995 – “Archaeological Resource Evaluation of Noranda Mines Mineral Exploration Areas at Jonathon and David Islands, Nain, Labrador.” Manuscript on File, Culture and Heritage Division, Department of Tourism, Recreation and Culture, St. John’s.

1997 – “Appendix to Maps: Thule-Labrador Inuit Grave Sites. Sites of Religious or Spiritual Significance Component, LIA Land Claims Negotiations.” Manuscript on File, Land Claims Negotiations Office, Labrador Inuit Association, St. John’s.

Johnson, J. Peter

1985 – “Geomorphic Evidence for the Upper Marine Limit in Northern Labrador,” in Our Geographic Mosaic: Research Essays in Honour of G. C Merrill, D.B. Knight, ed., pp. 70-91. Carleton University Press, Ottawa.

Kaplan, Susan A.

1983 – “Economic and Social Change in Labrador Neo-Eskimo Culture.” Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr.

Lazenby, M.E. Colleen

1980 – “Prehistoric Sources of Chert in Northern Labrador: Field Work and Preliminary Analyses.” Arctic 33:628-645.

Nagle, Christopher

1978 – “Indian Occupations of the Intermediate Period on the Central Labrador Coast: A Preliminary Synthesis.” Arctic Anthropology 15(2):119-145.

1984 – “Lithic Materials Procurement and Exchange in the Dorset Culture Along the Labrador Coast.” Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Brandeis University, Waltham.

Periodical Accounts Relating to the Missions of the Church of the United Bretheren Established Among the Heathen

1837 – Letter from Hebron. Volume 14:219.

Taylor, J.G.

1974 – Labrador Inuit Settlements of the Early Contact Period. Publications in Ethnology No. 9, National Museums of Canada, Ottawa.

1988 – “Labrador Inuit Whale Use During the Early Contact Period.” Arctic Anthropology 25(1):120-130.

Taylor, J.G. and H.R. Taylor

1977 – “Inuit Land Use and Occupancy in the Okak Region, 1776-1830,” in Our Footprints are Everywhere, C. Brice-Bennett ed., pp. 59-81. Labrador Inuit Association, Nain.

Thomson, Callum

1986 – “Caribou Trail Archaeology: 1985 Investigation of Saglek Bay and Inner Saglek Fjord,” in Archaeology in Newfoundland & Labrador, 1985, Jane Sproull Thomson and Callum Thomson, eds., pp. 9-53. Historic Resources Division, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s.

Way, J. Edson

1978 – “An Osteological Analysis of a Late Thule/Early Historic Labrador Eskimo Population.” Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto.