Pierre Bibeau

Introduction

Project Context

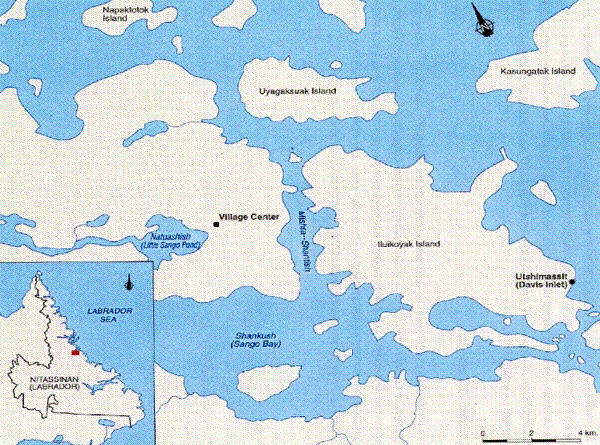

The Mushuau Innu community of Utshimassit (Davis Inlet), comprising a population of about 520 individuals, is located on Iluikoyak Island, off the coast of Central Labrador (Figure 1). The first families began to settle this site in 1967, under the initiative of the provincial government and of the Roman Catholic Church; these Innu had previously lived on the coast of Labrador, a few kilometres south of the new location, close to a former trading post (Whitford Env. Ltd, 1995:1).

Ever since its settlement, the community’s location has proved inadequate for the population for different reasons: very little land was available for building, drinking water was scarce, it was impossible to install a sewer system, and it was all but impossible to access inland hunting grounds during the spring and fall. Numerous health and social problems resulted from this situation (ibid.).

In 1993, the community accepted, through a referendum, a proposal by the Mushuau Innu Band Council to relocate to a new community on the mainland, at a location known as Natuashish (Little Sango Pond), rather than attempt to make Utshimassit (Davis Inlet) more liveable. In 1994, the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and the Federal Cabinet recognized the desirability of moving the community to Natuashish, provided, among other things, that the building and development of the new site be respectful of federal and provincial government standards, and that the costs be acceptable to Canada (U.M.A. Group, 1994:6).

The project’s approval has resulted in several studies, during 1994 and 1995, to assess its impact and its technical, environmental, cultural, and social feasibility. One of these studies was aimed at gauging the potential consequences of this development project on heritage resources, mainly through a review of background data (Whitford Env. Ltd, 1994). No photo-interpretation or selection of areas with an archaeological potential was performed at that point. Nevertheless, this study concluded that “it is considered essential that a complete archaeological field survey be conducted prior to site preparation for the new town site and related facilities” (ibid.:14).

The archaeological survey conducted during the summer of 1996 by Arkeos Inc. followed some of the recommendations stated at the outset of Phase 1.

Study Area

Utshimassit (Davis Inlet) is located on Iluikoyak Island, off the coast of Labrador, approximately 295 km north of Goose Bay and 85 km south of Nain (Figure 1). The new community at Natuashish will be located on the mainland of Labrador, on the northeast shore of Natuashish (Little Sango Pond), and just north of Shankush (Sango Bay). Natuashish is about 15 km west of Iluikoyak Island.

Figure 1. Map of the Study Area.

Fieldwork (Archaeological Survey)

The initial step of the archaeological survey consisted of a visual inspection of the area, to uncover any evidence of past human activity. At this stage, the archaeologist performed a meticulous search of all areas where surface deposits had been disturbed, either naturally (i.e. because of erosion) or as a result of human activity (i.e. footpaths). This reconnaissance of the area and of its topographic features also allowed the archaeologist to choose the location of future test pits.

Generally, test pit sites were chosen in areas with little or no slope and with good drainage. The vegetal cover generally consisted of black spruce and cladonia moss (caribou moss). Only the sections near the wharf and the gravel pit show large outcrops.

Depending on the local topography, test pits were made systematically every 10 to 15 m, or further apart where the ground was uneven. Test pits ranged between 40 and 50 cm across and their depth rarely exceeded 20 cm.

Whenever a site was discovered, its area, importance and condition were first assessed through supplemental test pits dug around those where archaeological remains had been found. The number of test pits had to be sufficient to provide a good evaluation of the site, without being so large as to unnecessarily spoil it.

Although no special efforts were made, numerous recent Innu campsites were discovered as we travelled the area, mostly on the northern shores of Natuashish and of the brook flowing into Natuashish.

Environment

The site to be developed at Natuashish (Little Sango Pond) community is located on the east coast of Labrador, on the 55th parallel, between the communities of Nain and Hopedale. More specifically, the proposed town site is located 15 km northwest of Utshimassit (Davis Inlet), in Labrador. The proposed site consists of a peninsula protected from the Atlantic in the lee of Iluikoyak Island to the east, and included between two long and narrow bays, north and south, providing easy access for shallow-draft seagoing vessels.

Vegetation

An open taiga-type spruce stand with Cladonia moss dominates, with black and white spruce dotting the valleys and sheltered areas. Larch or balsam fir are sometimes encountered, along with dwarf birches and willows.

The locally dominant vegetal cover includes mosses, lichens, spruce and fir, with rare white birches. The aerial photographs show that the sheltered hillsides are generally more densely wooded, as well as the areas skirting the bogs. From this, it may be reasonably deduced that these wooded areas possess a better developed root system than those more exposed to the prevailing winds or clinging to rocky outcrops.

A Brief History Of The Peopling Of The Central Labrador Coast

Archaeological research on the coast of Labrador dates back to Fitzhugh’s studies in the 1970s (Fitzhugh 1972). Many other scholars have followed suit, along the coast of Labrador, in Newfoundland and along the strait of Belle Isle (Loring 1989, and Pintal 1989). Certain coastal areas have been favoured. The Hamilton Inlet area is well-documented, and so is the coast of Labrador North of Nain. The Davis Inlet area, as well as the Central Labrador coastal area, are a little less known archaeologically. Research paradigms have mainly delved into economic adaptations along the seaboard, neglecting the harvesting of inland resources. This has led to an important knowledge gap, as many authors consider caribou hunting a recent occurrence (Denton 1989, McCaffrey 1989, Loring 1988, Samson 1983), and as archaeological cultures are largely defined by ways of life.

A research strategy aimed at exploring the hinterland would most certainly stimulate interesting debates and fill up some of the gaps. The work undertaken on the proposed site for Natuashish constitutes, for the time being, a modest contribution to knowledge about the Innu’s use of inland areas. A more systematic archaeological survey of promising areas would certainly lead to a better understanding.

This section deals with the prehistory of the Innu and the Inuit. However, the emphasis is put on Innu prehistory, as the area under study seems to have been more intensely settled by related groups (Loring 1988, Fitzhugh 1972).

Many scholars have contributed to the knowledge of the native cultures that settled the Labrador coast before the arrival of ‘white’ people, but it is undoubtedly Fitzhugh (1972) who most influenced archaeological research by proposing cultural and archaeological sequences. As discoveries progressed, many archaeological cultures were characterized on the basis of their chronologies and their ways of life. Thus, the first settlement of Labrador by natives can be traced back to about 8000 years. Many other cultures came after, or changed their habits in ways that led archaeologists to group them under different names. In the simplest of classifications, the American Indian occupation has been divided into three main groupings: the Maritime Archaic includes the period from 8000 to 3700 years B.P.; the Intermediate Period, which refers to a time frame between 3000 and 1750 years B.P.; and finally, a Late Prehistoric Period that covers the interval between 1000 to 400 years B.P.

The Inuit occupation of Labrador is more recent than that by American Indians. The first Inuit settled the area around 4000 years ago. As is the case for the Innu, archaeologists have characterized many different Inuit cultures. A somewhat schematic overview of the cultural chronology of the Inuit settlement leads to the identification of two main periods, the oldest of which is called the Palaeo-Eskimo, and extends between 4000 and 500 years B.P., followed by the Neo-Eskimo who are the forebears of the present-day Inuit.

The following sections describe in more detail these cultures and attempt to answer questions about the origins, the ways of life, the geographic distribution and the time frame of these peoples. They also deal with the cultural relationship between them.

Innu Prehistory

The first settlement of America dates back to at least 12,000 years, although an estimate of 18,000 years is becoming increasingly probable, and dates as remote as 40,000 years have been suggested, although without proof. These first native populations were named Palaeo-Indians by archaeologists. Some traces left by these populations may be found in the southern fringe of Labrador. At this time, no such evidence has ever been found in Labrador. In Nova Scotia, the discovery of the Debert site, dating back more than 10,000 years, was one of the first definitive testimonies to a Palaeo-Indian occupation of the American northeast (MacDonald 1985). A few projectile points, characteristic of the techniques used by these cultures, were found in New Brunswick and on Prince Edward Island. Unfortunately, these objects were not associated with any archaeological context, which greatly limits their value as archaeological interpretation tools (Keenlyside 1985). Other evidence of a Palaeo-Indian occupation was found in areas closer to the southern fringe of Labrador, namely in Gaspé (Benmouyal 1987) and in Rimouski (Chapdelaine 1994). They are linked to the Plano culture, one of the several Palaeo-Indian cultures that travelled through the American Northeast between 8000 and 10,000 years ago (Ellis and Deller 1990).

The first archaeologically well-documented American Indian occupations are attributed to the Maritime Archaic period. As defined by Fitzhugh (1978a), it includes four different cultural phases (Table 1). The most ancient phase was mainly documented through the Hound Pond site, in the Hamilton Inlet area, but the earliest evidence for Maritime Archaic occupation is found in southern Labrador. According to the latest archaeological data, the Maritime Archaic populations mainly relied on Labrador’s coastal resources, between the Hamilton Inlet area to the south, and the Nain-Okak area to the north. Very little is known about a possible settlement inland, but some evidence was found at Indian House Lake (Samson 1978, 1983). Many food remnants evidence a regular consumption of sea mammals (seal, walrus) and fish. This type of economy is also suggested by the presence of certain tools, such as toggling harpoons. The locations of the Maritime Archaic sites are indicative of a preference for inlets, islands and sandy beaches as settlement areas. Because of the post-glacial uplift of the earth’s crust, numerous Maritime Archaic sites are now located on uplifted terraces, with elevations ranging from 20 to 28 m above today’s sea level. This American Indian culture cannot be identified in Central and Northern Labrador after 3500 years B.P. Its disappearance from the seaboard may be related to the arrival of Inuit groups.

Archaeologists, then, distinguish many cultures with similar features and group them according to these similarities into the important Intermediate Period. These cultures differ in traditions and ways of life a from those of the Maritime Archaic period. However, scholars seem to think unanimously that they are the direct forebears, through the Point Revenge culture, of today’s Innu. Their means of subsistence were not very different from those of the Maritime Archaic cultures, although they relied heavily on inland resources. Although not much is known about the reliance on inland animal resources, we have a clearer picture of their reliance on inland resources for raw materials. While Maritime Archaic populations had mostly used Ramah quartzite or chert (the main source of which is located between Saglek and Nachuak), Intermediate Period populations used a variety of materials gathered inland (Loring 1989). Like the Maritime Archaic peoples, they also preferred to settle on sandy beaches, at the back of small coves or next to inlets. During this period, the first contacts between American Indians and Inuit are abundantly evidenced. Certain stone tools were used to barter with other American Indian groups living much farther south as far as Quebec City (Loring 1989). Similarities in settlement patterns and technology seem to witness a cultural continuity between the Intermediate Period American Indians and today’s Innu. This continuity is best documented for the Point Revenge culture of the Late Prehistoric Period.

Table 1. Chronological Periods and Cultures Related to Innu Prehistory.

| Maritime Archaic | Intermediate Period | Late Prehistoric Period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | Dates | Culture | Dates | Culture | Dates |

| Hound Pond | 7500-7000 yrs BP | Little Lake | 3600-3200 yrs BP | Mishta-Shanipass | 1700-900 yrs BP |

| Sandy Cove | 600-4500 years BP | Saunders | 3500-2800 yrs BP | Point Revenge | 900-600 yrs BP |

| Black Island | ca 4200 years BP | Brinex | 3200-3000 yrs BP | ||

| Rattlers Bight | 4100-3800 yrs BP | Charles | 3000-2700 yrs BP | ||

| Road | 2700-2300 yrs BP | ||||

| David Michelin | 2300-1800 yrs BP | ||||

| North West River | 1800-1400 yrs BP | ||||

| (from Fitzhugh 1978a,Nagle 1978, Loring 1988) | |||||

The Late Prehistoric Period is mostly documented through the Point Revenge culture. Many small sites from this culture have been found from North West River and Groswater Bay to Nain (Fitzhugh 1978b). Point Revenge occupations have also been discovered along the strait of Belle Isle (Pintal 1989). Settlement and subsistence activity patterns are similar to those described for the Naskapi in the 19th Century (Loring 1989, Turner 1979, Speck 1977). Unlike the Intermediate Period cultures, a return to a preferential use of Ramah chert is noticed. The northward expansion of the Point Revenge culture coincides with a withdrawal of the Inuit populations, but around 500 years B.P., the arrival of the Thule culture (modern Inuit) somewhat stopped this American Indian northward expansion.

The Daniel Rattle Complex, as defined by Loring (1989), represents the earlier half of the recent Indian period, before Point Revenge.

Innu Prehistory

Archaeological known sites from Labrador were chosen on account of their locations relative to that of Natuashish. A radius of about 40 km, centred on Natuashish, was thus defined (Figure 2). From information provided by the Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, we were able to locate 37 known sites within that area (Figure 2). Taking into account the cultural components rather than the sites themselves, as many sites possess different components, 26 Innu occupancies were found, including 19 prehistoric and 7 recent occupancies; there were also 13 Inuit occupancies, 11 prehistoric and 2 recent; and, finally, 3 sites could not be attributed with certainty to any one culture. These data indicate prehistoric and recent presences in the vicinity of the area under study, representing all major American Indian cultural phases. But again, very few sites are known inland.

Near the area under study, four new sites were discovered. The Daniel Rattle Site #1 (GlCg-1) evidences a Maritime Archaic component, whereas the Daniel Rattle site #2 (GlCg-2) with its specific artifacts, was used to define a complex associated with that of Point Revenge. The excavation of site GlCg-1 uncovered the first longhouse (Shaputuan) on the coast of Labrador (Loring 1984). The Sango Mountain Stream site (GlCh-1) yielded a fireplace, one flake and an historic tent structure. This material is insufficient to adequately define occupation. The Nancy Flowers Cabin site (GlCh-2) evidences Inuit and Innu historic presences.

Figure 2. Location of Archaeological Sites.

Inuit Prehistory

The Inuit occupation of Labrador is archaeologically better documented. Numerous cultures were identified and may be grouped in two major periods (Table 2). The Early Palaeo-Eskimo cultures mostly settled Northern Labrador, between Hebron and Nain (Fitzhugh 1980). Some sites may, however, be found further south, as far as the Hopedale area and even as far as Seven Islands, in Quebec.

The Groswater culture seems to have had a wider geographical extent, as it mainly settled the north, between Nain and Hamilton Inlet, but also as far south as Blanc Sablon (Pintal, 1989). Sites attributed to the Late Palaeo-Eskimo (Dorset culture) are more numerous. Compared to American Indian populations, the Inuit favoured seal hunting more than hunting other mammals, and their preferred environment was the coast.

Table 2. Chronological Periods and Cultures Related to Inuit Prehistory.

| Early Palaeo-Eskimo Period | Late Palaeo-EskimoPeriod | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | Dates | Culture | Dates |

| Early Pre-Dorset | 3800-3500 years B.P. | Labrador Early Dorset | 2500-2000 years B.P. |

| Late Pre-Dorset | 3500-3200 years B.P. | Middle Dorset | 2000-1400 years B.P. |

| Transitional Pre-Dorset | 3200-2800 years B.P. | Late Dorset | 1000-650 years B.P. |

| Groswater Pre-Dorset | 2800-2200 years B.P. | ||

| (from Fitzhugh 1980) | |||

Known Sites in the Natuashish Area

In the area surrounding Davis Inlet, Inuit sites are mainly found on islands at the northern and southern limits of the area under study (Figure 2) . Inuit occupation in the immediate vicinity of Davis Inlet is little known at this moment.

History of Utshimassit (Davis Inlet)

Innu history was not much documented by Euro-Canadians before the end of the 19th century (Armitage 1990, Turner 1979, Speck 1977, Henriksen 1973). There was even much confusion about the names of native groups that lived in what is now called the Quebec-Labrador Peninsula (S.A.G.M.A.I. 1984, Mailhot 1983, Turner 1979). Today, the Utshimassit Innu consider that they belong to the Innu Nation and call themselves Mushuauinnut (Whitford Environment Ltd., 1994).

The establishment of trading posts did not convince the Innu to take an active part in trapping fur-bearing animals. For the Innu, caribou hunting remains the main activity. For them, caribou possesses economic, social and religious values. This kind of dependency was to be the cause of problems at the outset of the 20th century. At that time, there was a noticeable decline in the caribou population that forced the Innu, who lived in the Indian House Lake area, to migrate towards the coast (Henriksen 1981) and settle near the Davis Inlet trading post around 1916. Along with the caribou shortage, that period saw the Innu’s most plentiful hunting grounds being invaded by non-natives (Armitage 1990).

In 1948, the Government of Newfoundland tried unsuccessfully to have the inhabitants of Utshimassit move to Nutak. After that, the government tried to integrate the Innu by providing them with a school system and means of transportation to help them go hunting and trapping inland. The settlement of the Innu in communities may be easily explained by numerous historical and socio-economic factors that have upset their traditional ways of life and disturbed their state of health. These conditions led to the Innu’s increasing dependence on government help.

The present community of Davis Inlet was founded in 1967. Settlement in such an isolated location, and the reliance on the Euro-Canadian market economy, led to internal conflicts among the Innu, as they feel caught between their traditional sharing values, which are perpetuated during hunting, and the possibility of acquiring goods and services through paid jobs. Psychological, social and economic stresses followed, which led to family feuds and substance abuse. One of the main goals of the development of Natuashish is precisely to favour settlement in an environment where traditional values can be expressed freely again.

Figure 3. GlCg-8 Site: Soil Profile, Test Pit A, east wall.

Archaeological Survey At Natuashish

Road, Waterline and Oil Pipeline

The proposed road covers a distance of about 9 km, and runs from the airstrip to the location of the wharf, on the shore of the Mishta-Shantish (Daniel Rattle). Conducting test pits along the road proved difficult at first, as its alignment had not yet been finalized. Changes in the alignment resulted in the unnecessary survey of a few areas. Finally, a preliminary alignment was staked by the surveyors, spanning the entire distance between the airstrip and the wharf. Our survey is based on this alignment, but some further surveys may ultimately be required if the alignment is moved again.

Vegetation, topography and drainage are very diverse along the proposed road. It covers level and uneven tracts of land, including outcrops, bedrock, and areas strewn with boulders, wooded areas and others, in the vicinity of water, where a dense and poorly drained riparian ecotone can be found: boggy, waterlogged areas, as well as sandy, well-drained ones.

The pedology observed in the test pits is characterized by a podzol similar to that often observed in the boreal forest. The vegetal cover is mostly composed of cladonia (caribou) lichen, and of berry bushes (blueberries, blackberries, etc.). Under the vegetal cover lies the A0 horizon, consisting of decomposing vegetal matter (see Figure 3). This matter includes poorly humified wastes, roots, and rootlets. The thickness of this horizon ranges between 5 and 10 cm, with an average of 8 cm. Under horizon A0 lies horizon A1, which is a black, organic topsoil. It is always thin, not over 0.5 cm, (and non-existent in some areas). Horizon A2 lies under horizon A1. This layer is impoverished by leaching, has a grey colour and a thickness range of 0.5 to 1.5 cm. Horizon B, located under Horizon A2, consists exclusively of mineral matter. Its reddish colour denotes the presence of iron. We have excavated through this horizon to depths ranging from 5 to 10 cm.

Test pits were first conducted in the vicinity of the airstrip and, from there, all the way to the wharf. Generally, that part of the road that leads from the proposed town site to the wharf covers an area much less conducive to human occupation. The road hugs the hillsides and runs over swampy or uneven tracts of land. From the airstrip to the proposed town site, many areas were more systematically investigated.

From the airstrip, test pits were conducted on the terraces leading to the many brooks that flow into Natuashish (Little Sango Pond). Between the site of the airport and the location of the proposed village site, 130 test pits were excavated, but none yielded any archaeological material.

Some more promising areas to the north of the site of the village were investigated with test pits every 10 m along four parallel lines. No artifacts emerged from the 120 test pits that were excavated in this area. However, at a place where the road alignment crosses a bigger brook, about 0.75 km north of the proposed town site, three sites were discovered. Two of them (NAT-17 and NAT-18) include recent dwelling structures, and the third (GlCg-8, designated NAT-19 in the field) is a prehistoric site.

- NAT-17 (13N/04 Ethno 10)

Site NAT-17 includes seven tents, located about 50 m south of a small brook, on its left shore. The distance from this site to the proposed alignment of the road is about 20 m. The dwelling structures are rectangular and measure between 5.5 x 5 m and 3.4 x 2.8 m. Many poles are still present and most tent structures have spruce-covered floors. The area is swampy, suggesting winter occupation, which is confirmed by the presence of snowshoes, snowmobile parts, and pegs that were used as stove supports inside the tents. Many test pits were made in the immediate area around the campsite, but all proved negative. - NAT-18 (13N/04 Ethno 11)

Site NAT-18 is located on the right shore of the same brook where site NAT-17 was discovered. The area of site NAT-18 includes at least 20 dwelling structures. One of the structures was used as a church, according to one of the archaeological surveyors. A large wooden cross also stands by the brook. Site NAT-18 starts from the side of the brook and extends north all the way to a hillock. Many test pits were conducted on this hillock, but no artifacts were found. - GlCg-8 (NAT-19)

North of site NAT-18 is a terrace running east-west at an elevation of 10 m above sea level (a.s.l.). In that area, test pits were systematically excavated every 10 m along four parallel lines. Site GlCg-8 (formerly designated NAT-19) is located on the terrace, 4.4 m away from the centre line of the proposed roadway and 2 m away from the incline. One test pit yielded two stone flakes made of Ramah quartzite from horizon A1. Close to 80 more test pits were dug in the surrounding area, covering the terrace, the slope, and the inside of the terrace. A second test pit, close to the positive one, yielded one hyaline quartz flake from the greyish horizon. Some 30 m northwest of the positive test pits, there is a recent dwelling structure. To summarize, this area was thoroughly investigated with some 250 test pits. Of that number, only two yielded artifacts.The remaining part of the road alignment, up to the wharf on the Mishta-Shantish, lies in an archaeologically less interesting area. It mostly runs along hillsides with bare bedrock and boulders, and enters a wooded and swampy area that leads to the hill where the quarry will be located, near the proposed location of the wharf. Only a small plateau, near a brook, was tested systematically. Around 25 test pits were excavated, but no artifacts were discovered.In conclusion, over 600 test pits were excavated along the road alignment. The survey of that area located three sites, one of which (GlCg-8) exhibited a prehistoric component.

Water Reservoir

The water reservoir area was only inspected visually. It is located on a 50 m high hill, the contours of which are ragged. No test pits were excavated because the area is swampy with uneven topography. No archaeological sites were discovered there.

Power Plant and Fuel Storage

This area is generally swampy. Test pits were nevertheless excavated where the drainage seemed to be adequate. No prehistoric or recent artifacts were found.

Sanitary Landfill

This area is located on a hillside, south of the road layout. The sanitary landfill will be located south of the road, in a swampy area. No test pits were conducted in that area, except on a small terrace further north that was described above. No remains were discovered.

Sewage Treatment Site

The location of the sewage treatment site is not the same as that provided to us initially. The new site consists of a rectangle located within a swampy area south of a small lake and east of a hill overlooking the Mishta-Shantish. A visual inspection of the area did not justify any test pits because of the swampy nature of the area. Only a visual inspection was conducted for that area, and no remains were identified.

Quarry and Borrow Pit

It is estimated that 700,000 tonnes of borrow and aggregate materials will be required to construct the various infrastructure such as roads, airstrip, wharf, building foundations, at the new community (Newfoundland Geosciences Ltd., 1994). The results submitted by Newfoundland Geosciences Ltd. show that five areas could be used as borrow pits or quarries.

Only two of these areas were included in the archaeological survey area. They are areas 35C for the borrow pit and R3 for the quarry, as identified in the Newfoundland Geosciences Ltd. report (1994). Area 35C consists of a hill whose subsurface is characterized by fine sand and gravel. It is located on an approximately 50 m high hill (a.s.l.), north of the airstrip. Area R3 is a quarry site with a rockier subsurface. It is located on a hill, southeast of the wharf, near the shore of the Mishta-Shantish.

On the top of the hill designated 35C, which is designated as a future borrow pit, a few ten centimetre-sized rocks can be seen. At first sight, these rocks seem to be arranged in more or less circular patterns. The first pattern measures 1.78 m x 1.55 m, with the long axis oriented in a north-south direction. The second pattern is more truly circular and has a diameter of 2.1 m. The area was fairly eroded, and a meticulous visual inspection, as well as a few test pits, did not yield any cultural evidence. In light of these results, those patterns were not deemed to be archaeological sites, but their shapes remain puzzling.

The hilltop and many terraces were visually inspected, notably the eroded areas, and test pits were made (about 70). No archaeological sites were discovered in that area. The observed pedology is characteristic of a podzol. The R3 area, designated as a quarry site, appears to be very uneven. Generally, the hillsides show an uneven surface that is shaped by a subsurface that consists of large boulders piled up in a disorderly manner. A few small areas were nevertheless sounded (around 15 test pits altogether), but no sites were discovered.

Wharf at Mishta-Shantish (Daniel Rattle)

The wharf is located on the western bank of Mishta-Shantish. The area consists of three small rocky capes protruding into the straits. The wharf will be built on the middle cape. A prehistoric site that includes a historic component (GlCg-7) was discovered on the rocky cape that lies south of the wharf.

- GlCg-7 (NAT 6)

Site GlCg-7 (formerly designated NAT-6) is located about 20 m from shore. Its elevation is a modest 3 m above the water level. The site is located in a small clearing, north of the cape, that slopes gently towards the shore. It includes a dwelling structure (# 1) discernible as a circular or oval stone pattern with a discontinuous peripheral 10 cm high rim. The exact contour of the structure, however, is not well defined, and two sizes are possible. It could be either 4.3 m long (north-south axis) by 3.3 m wide (east-west axis), or 5.8 m long (north-south axis) by 3.3 m wide (east-west axis). However, it seems that the 4.3 m x 3.3 m measurements are the most probable. This hypothesis is supported by the more or less central location of a 1.5 m (east-west axis) by 1 m (north-south axis) hearth.At one end of that fireplace, a test pit confirmed its identification (presence of charcoal) and yielded about 40 different coloured glass beads. These beads would be consistent with an occupation of the site around 100 years ago. A particular feature of this structure is a heap of stones (10 to 15 small boulders) at its northern end. As a matter of fact, these stones are what prevented us from finding out the precise measurements of the structure. Also, that end of the structure is hidden under a thicket of evergreen. Immediately east and west of Structure # 1, two possible tent sites are present. At this time, they are not considered to be dwellings. On the east side of Structure # 1, a shallow depression in the ground could be indicative of a 2.5 m diameter circular structure. The inside of the depression is covered with caribou moss, whereas its immediate surroundings are mostly covered with peat (sphagnum) moss.West of Structure # 1, an oval shape, measuring 4.5 m by 3.2 m, was also noticed on the ground. Its perimeter is suggested by a discontinuous line of stones. A few evergreen trees have grown in that location.Site GlCg-7 also includes a more recent occupation area. About 20 m west of Structure # 1, a group of three tent sites was found. They are located in a small clearing that connects west with a wooded area consisting of evergreen trees, and overlooks a swampy area on the north side. These recent tent sites are numbered 2 to 4. Structure # 2 is 4 m long (east-west axis) by 3.6 m wide (north-south axis); Structure # 3 has an east-west axis measuring 4 m and a north-south axis of 3.8 m; finally, Structure #4 measures 3.8 m east to west by 4.2 m north to south.A fifth structure (# 5) is linked to site GlCg-7. It is an oval structure, with a major axis (east-west) of 4.6 m and a minor axis (north-south) of 3.8 m. It is located about 60 m north of Structure # 1 and about 15 m from the shore. At that place, the elevation is only a metre or so above the water level.About 40 test pits were excavated in the survey area, three of which yielded artifacts. Test Pit B, at the edge of the fireplace, led to the discovery of beads; Test Pit C, a few metres away from the fire-place, yielded a Ramah quartzite flake, and a last positive test pit (A), containing a hyaline quartz flake, is located close to three recent dwelling structures.The 43 beads found in the excavated portion of the fireplace in site GlCg-7 show a great diversity of hues. The beads are ring-shaped, i.e. their diameter is larger than their length [1]. Pink and blue colours are most plentiful, but this result may be biased, as the fireplace was not completely excavated. In light of the variations in hues and the small size of the beads and, mainly, of the low elevation of this site above the water level, it is logical to believe that these beads date back to the turn of the century. Unfortunately, we do not have any comparative data at this time. - NAT-8 (13N/14 Ethno 5)

An occupation area was identified in site NAT-8. It consists of three recent tent sites, located in a swampy area, about 40 m away from Structure #1 in site GlCg-7. It contains many empty preserve cans, pieces of clothing and gasoline cans. In the vicinity, some trees were cut about 0.4 m off the ground, suggesting a winter or spring occupation. About ten test pits excavated in the area did not yield any artifacts. The topsoil has all the characteristics of a podzol.

Airport

The area considered for the airstrip is roughly 1.7 km long by 0.4 km wide. The runway axis will be oriented to 300°. Its location is on a long, even tract of land, skirted on the north side by a hilly area. Before the archaeologists arrived, land surveyors had already staked the runway’s centre line. At first sight, this area shows good archaeological potential. The topography is generally flat, and the drainage is excellent. A first series of test pits was established from point 0 + 520 m of the land survey, as the ground is swampy and uneven east of that point. The test pits were conducted along four parallel lines 10 m apart. Along each of these lines, test pits were made every 10 m or so, depending on the topography. Most test pits were excavated to a depth of 15 cm, with some down to 40 cm, to attempt to find buried habitation sftes. About 180 test pits were excavated, but none led to the discovery of a site.

Boat and Float Plane Wharves

These areas are located on the northwest shore of Natuashish (Little Sango Pond), on either side of a small headland projecting into the pond. This headland is favourable for human occupation, as is the shore of the small bay bordered by the north side of that headland. At a meeting with the Band Council in Utshimassit (Davis Inlet), we were told by many Mushuau Innu that this area was frequently used by them.

As construction work was planned for that area and as we were able to survey it without delaying our mandate, we thought that it would be of use to excavate a few test pits there, even though the area was not a priority.

The survey allowed us to verify the validity of the information gathered during our meeting with the Band Council. Recent Innu presence is evidenced by five sites (NAT-1, NAT-2, NAT-3, NAT-4 and NAT-7), while a sixth site GlCh-3 (formerly designated NAT-5) shows the presence of an earlier occupation, probably dating back to pre-European times.

- NAT-1 (13N/14 Ethno 1)

Three dwelling structures were found along the sandy ridge that overlooks the small bay. The first site (NAT-1) includes a rectangular dwelling structure located about 35 m away from the northeastern end of the shore. The structure is shaped like two rectangles joined back to back. Its dimensions are 3 m along its northeast-southwest axis and 3.7 m along the northwest-southeast axis. There are no spruce-covered floors, poles or pegs. About 7.5 m west of the structure lie a dozen poles and a few pegs, most of which are scorched. - NAT-2 (13N/14 Ethno 2)

Site NAT-2 is located on the southern side of the headland, across from a swamp. It includes three dwelling structures located from 7 to 23 m away from the shore. Structures # 1 and # 2 are close to each other and near a wooded area, while Structure # 3 is much farther, about 40 m south of Structure # 2. Structure # 1 is characterized by a shallow oval or rectangular depression filled with evergreen branches. It is located on the sandy beach and its dimensions are 2.6 m along its northeast-southwest axis, and 3.5 m along its northwest-southeast axis. Structure # 2 is located 10.5 m west (258°) of Structure # 1. It has a square shape, and its floor is also covered with evergreen branches. An exterior fireplace is located about 1.2 m to the northeast, towards Natuashish (Little Sango Pond). Structure # 3 is off set from the other two. It is identified by the presence of grooves in the ground that were left by the structure’s frame. It has the shape of two contiguous squares and measures 2.35 m along its north-south axis (4.7 m when both squares are considered) by 3.5 m along its east-west axis. There are no remnants of a hearth or of an evergreen floor cover. The three structures have no poles. - NAT-3 (13N/14 Ethno 3)

Site NAT-3 is far more imposing than sites NAT-1 and NAT-2. It is located at the tip of the headland and also occupies part of its southern shore. Structures and other areas of interest are scattered on an incline that runs from the beach to the riparian ecotone. The environment consists mainly of a cladonia lichen-covered clearing. Shrubs and black spruce are also found in places.Site NAT-3 covers an area measuring about 120 m (east-west axis) by 40 m (north-south axis). A quick visual inspection allowed us to identify at least 25 dwelling structures. The ground is covered with rubbish, including preserve cans, pieces of cloth, shoes, diapers, etc. Distances between the structures and the shore range from 3 m to 40 m. According to the state of the preservation of the structures, there may be a wide range in the dates of the site. The structures nearest to the tip of the headland seem to be more recent. Generally, these structures are square and have evergreen-covered floors. Some display oval or rectangular contours. Many also have short pegs used as stove supports. Secondary structures associated with the dwellings are fireplaces, smokehouses, fish-drying structures, and also a wooden toilet. Finally, it is possible that some structures were overlain, the more recent having partly destroyed the older. This suggests that the site was regularly occupied at different periods. - NAT-4 (13N/14 Ethno 4)

Site NAT-4 runs along the southern shore of the headland and is located about 80 m west of site NAT-3. It includes at least 18 recent dwelling structures that are located about 40 m from shore, between the riparian ecotone and the terrace. It should be noted that there are probably more structures between sites NAT-3 and NAT-4. These structures have different shapes and are in varying states of preservation: some look quite ancient and are hardly noticeable; others are more recent, as indicated by the debris (diapers, rusty cans, batteries, etc.) littering the ground. Skidoo parts and the fact that some trees were cut 1.6 m above the ground suggest winter or spring occupancies. - GlCh-3 (NAT 5)

Site GlCh-3 (formerly designated NAT-5) is located on a terrace, 10 m a.s.l., that runs along the small cove that borders the northern shore of the headland. That area is moderately wooded, and long tracts are covered solely by cladonia lichen and berry bushes. Test pits were conducted along three parallel lines, 10 m apart, for a total of 125 test pits. Two of those test pits yielded one Ramah quartzite flake each.Test Pit A is located about 25 m from the edge of the terrace, and test pit B sits about 8 m from this edge. In both cases, the flakes were found at the interface between black (A1) and grey (A2) podzol horizons. - NAT-7 (13N/14 Ethno 17)

Site NAT-7 consists of a dwelling structure located near the beach, at the foot of the terrace where Test Pit A of site GlCh-3 was excavated. Occupation could be quite ancient, as a 5 m tall tree has grown inside the structure. The outline of the structure is more or less circular, with a diameter of about 3 m.

To summarize, for the general area of the headland, about 300 test pits and a systematic visual inspection led to the discovery of six sites, one of them having a prehistoric component.

Water Pump

The proposed site for the water intake is located on the left bank of Sango Brook, approximately 800 m west of its mouth on Natuashish (Little Sango Pond). This area is not favourable for the presence of archaeological sites. It is low and very swampy. Only a visual inspection was conducted, and no cultural evidence was found.

Location of Recent Innu Sites – NAT-9 to NAT-16

- NAT 9 (13N/14 Ethno 6

- NAT 10 (13N/14 Ethno 7)

- NAT 11 13N/14 Ethno 8)

- NAT 12 13N/14 Ethno 18)

- NAT 13 13N/14 Ethno 19)

- NAT 14 (13N/14 Ethno 9)

- NAT 15 (13N/14 Ethno 20)

- NAT 16 (13N/14 Ethno 21)

A short survey along Sango Brook and around Sango Pond was conducted, using a motorized canoe, to locate recent structures. In the course of this visual inspection, which lasted only lasted a few hours, 8 sites were identified (NAT-9 to NAT-16).

Site NAT-9 is located northwest of Sango Pond and includes three dwelling structures. Site NAT-10 lies about 1 km east of site NAT-9 and consists only of a stone tent ring. Site NAT-11 is located close to the working camp, on the west side of it. It includes three dwelling structures, as well as a sweat tent. Site NAT-12 is located southwest of Natuashish (Little Sango Pond), at the mouth of Shankush (Sango Bay). It is a major recent occupation site, as it includes nearly 100 dwelling structures. Site NAT-13 sits across the mouth from site NAT-12. It includes at least five dwelling structures.

Site NAT-14 is located at the mouth of Sango Brook, on its northern shore. It includes six dwelling structures. Site NAT-15 is located on the north shore of Sango Brook and includes three dwelling structures. Finally, site NAT-16 is located between sites NAT-14 and NAT-15, on the north shore of Sango Brook. It includes two dwelling structures.

To summarize, although little attention was given to the shoreline of Sango Pond, many recent sites were seen, and it appears that this area was favoured for a good many years by the Innu.

Discussion

The archaeological survey conducted during the summer of 1996 allowed us to evaluate systematically all the areas included in our mandate. Depending on the topography and drainage, areas were subjected to test pits or visual inspections. About 1200 test pits were excavated in the area. Of that number, only 8 yielded archaeological artifacts (flakes and glass beads). 19 archaeological sites were identified. On the whole, there is ample evidence of recent occupancies of the area in the last 100 years. As for the three prehistoric sites discovered (GlCh-3, GlCg-7 and GlCg-8), it seems difficult to give them definite datings and cultural assignations, as only flakes were discovered. However, two of the sites discovered (GlCh-3 and GlCg-8) are elevated only 10 m a.s.l., on a terrace that was formed about 3300 to 4000 years B.P.

If these sites were occupied when the sea was nearby, they could be associated with the Intermediate or the Late Prehistoric periods. However, the fact that no diagnostic artifacts were discovered prevents us from establishing a definite cultural affiliation. In other respects, the diversity of raw materials used would suggest the Intermediate Period, as the Maritime Archaic and Point Revenge cultures relied more heavily on Ramah quartzite.

It is also interesting to note that, at this time, almost 40 sites are known within a 40 km radius of the proposed town site. The three prehistoric sites discovered during the summer of 1996 (GlCh-3, GlCg-7 and GlCg-8) may be related to inland transits. Sites evidencing more complex cultural activities (butchering sites, feast sites, communal hunting and ceremonial grounds, etc.) may be present somewhere inland.

Finally, the discovery of 16 recent occupation sites indicates a major recent presence in the area. Some were perhaps ceremonial sites. A church was built on site NAT-18, while sweat tents were identified at site NAT-11. All of this gives a high spiritual value to the area, and it may not be a coincidence that the Innu have chosen it for their new settlement.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The archaeological survey conducted during the summer of 1996 in the vicinity of the future community of Natuashish has met its stated objectives and has in a large part answered the recommendations, formulated as a result of Phase 1 of the Heritage Study, pertaining to the regulations under the Historic Resources Act (Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 1985).

Only the areas that will be directly affected by the first phases of construction had to be surveyed: the wharf and adjacent areas, the quarry and gravel pit, the airstrip and associated areas, the water intake, the reservoir site, the access road from the wharf to the airstrip and the alignment of the adjacent pipes, the site of the facultative lagoons, and the site of the solid waste disposal facility. The future village site itself, and several areas located in the vicinity of the development (on the shores of Natuashish (Little Sango Pond), Shankush (Sango Bay) and Mishta-Shantish (Daniel Rattle), which may be indirectly affected by the construction and operation of the community, as well as the location of the four already known archaeological sites (GlCg-1, GlCg-2, GlCh-1 and GlCh-2), were not considered in the 1996 season.

Notwithstanding the localized nature of the survey, the discovery of three prehistoric sites (GlCh-3, GlCg-7 and GlCg-8), as well as of sixteen recent Innu sites, adds significantly to the already known prehistoric sites (GlCg-1, GlCg-2, GlCh-1 and GlCh-2) and confirms the presence of native and Innu groups in prehistoric, historic and recent times. Prior studies, including Whitford Environment Ltd (1994, 1995) and Armitage (1990), had stressed the archaeological and historical value of the area surrounding Natuashish:

The Natuashish area has long served the Mushuau Innu as a traditional camp site and staging area for entering and leaving the country. (Whitford Env. Ltd, 1995:19)

The following recommendations take into account the laws and regulations protecting archaeological resources, the recommendations included in phase 1 of the heritage study, the results of the 1996 survey, and the expected impact of the development project on known and potential heritage resources.

Prehistoric Sites (discovered in 1996)

Three prehistoric sites were discovered during the survey: GlCh-3, located northwest of Natuashish; GlCg-7, located near the wharf, on the west bank of Mishta-Shantish (Daniel Rattle); and GlCg-8, along the road that will connect the wharf and to the airstrip, north of the community. Additional test pits were conducted in these areas to enable their evaluation. Based on these results, we recommend the following for the 1997 season:

1. For GlCh-3, no further excavation is proposed. Much effort was spent on this small site, where only two coarse stone flakes were found, and which does not seem to be directly threatened by the wharf’s construction.

2. GlGg-7 is located approximately 120 m south of the wharf, near a rock ledge along Mishta-Shantish (Daniel Rattle). Many components were identified: three recent Innu campsite locations, one historic dwelling structure of apparent Inuk origin, the central fireplace of which contained beads, and two positive test pits containing coarse stone flakes. It is also possible that the Inuk structure is surrounded by two other surface dwellings, one to the west and one to the east.Although it is not located directly in the area of the wharf, this site may, in our opinion, be threatened by the proximity of proposed development areas. Apart from the wharf itself, an access road will be built, and some buildings are likely to be erected in the vicinity. As a mitigation measure, we suggest that a second archaeological campaign be performed at site GlCg-7. Its objectives would be to completely excavate the inside of Structure 1 (where beads were found), to determine the possibility that the two neighbouring structures are indeed dwellings, and finally, to extend the excavated areas surrounding the two positive test pits to search for further remains.

3. As for site GlCg-8, the two positive test pits that led to its identification are located 4.4 m and 6.1 m, respectively, east of the proposed centre line of the road, as of August 1996. As in the case of GlCh-3, this is an interesting site, particularly given its geographical location: a former marine terrace (10 m) which was formed around 4000 years B.P. (according to a study by Clark and Fitzhugh 1991). As remedial measures, we recommend broader area excavation around the A and B test pits, so as to circumscribe the area containing remnants.

Recent Sites (discovered in 1996)

Although we did not endeavour to systematically locate every recent Innu campsite, we were able to demonstrate the proverbial expression “our footprints are everywhere,” as we identified sixteen recent campsites. Armitage (1990) and Loring (1984) had already noted the intense occupation of the Shankush (Sango Say) area in historic and recent times. It seems obvious that a systematic survey along the shores of Mishta-Shantish (Daniel Rattle), of Shankush (Sango Bay), and of Sango Brook would lead to the identification of several more sites. Three of those that we found look particularly interesting:

- NAT-12, at the southwest mouth of Natuashish (Little Sango Pond), where more than one hundred dwelling structures are visible;

- NAT-18, near a brook north of the community, which consists of a winter or spring campsite and includes a ‘church’;

- NAT-11, on the north shore of Natuashish (Little Sango Pond), somewhat west of a workers’ camp built where a sweathouse was found.

4. In our opinion, the emphasis to be placed on documenting the recent usage of the area should be decided jointly by the MIBC, the MIRC, and the elders of Utshimassit community (Davis Inlet). Should these sites be systematically surveyed and documented? Are some of them so important as to warrant special protection measures? Understanding how the area was settled, and how its resources were used in historical and recent times, is important if a full understanding of the indigenous settlement, including that of the shoreline and of the hinterland, is to be gained. This would also help prehistorians locate and understand prehistoric sites. The work conducted by Armitage (1990) perfectly illustrates this point, and certainly makes him a logical choice for coordinating a future ethnological survey of the recent sites in order to provide prehistorians with additional archaeological data.

Future Archaeological Surveys (1997 and beyond)

1997 Season

The 1996 survey only targeted the areas that are to be developed in priority from the 1997 season on. The location of these areas was based on the most recent data available at the time of the survey. Therefore, in addition to following up 1996 fieldwork our next recommendation is aimed at ascertaining that those areas where the 1996 fieldwork took place are still correct:

5. In the event that changes are made to the choice of development locations proposed in our 1996 mandate, archaeological surveys should be carried out in 1997, in the new locations, prior to construction.

6. We also recommend that a further archaeological survey be conducted during the summer of 1997 in the area that will be developed for the community of Natuashish itself, as well as in other areas to be developed, and that have not yet been surveyed.

7. Finally, also for the 1997 season, we recommend that an archeologist be present at the site to deal with unforeseen situations.

1998-2001 Seasons

Apart from the sites that were given priority in 1996, many areas remain threatened, directly or indirectly, by the construction and operation of Natuashish. Besides the obvious threat to the heritage resources located within the community itself, the whole area included, east to west, between Mishta-Shantish (Daniel Rattle) and Big Sango Pond and, south to north, between Shankush (Sango Bay) and Merrifield Bay is bound to have its heritage resources impacted by this project.

One must understand that most archaeological sites in the area, even those many thousands of years old, lie only a few centimetres below ground level, on account of the slow pedogenic process that exists in the boreal forest. Generally, the sandy deposits that contain artifacts are only protected by a thin layer of cladonia lichen. Any motor vehicle, including recreational four-wheelers, may destroy this fragile vegetal cover and disturb the underlying levels, leaving them unprotected from wind erosion. The imminent arrival of several hundred permanent residents increases the risk of unintentional destruction. Experience also shows that it is unrealistic to attempt to accurately delimit the sites to be developed: there are many instances where heavy equipment disturbed a larger area than expected during construction; or when supposedly protected sites are ultimately used. The possible negative impact of the new community on archaeological resources in the vicinity was underscored during Phase 1 of the Heritage Study (Whitford Env. Ltd, 1994:13). Consequently, we recommend:

8. That the archaeological survey between 1998 and 2001 should encompass a larger outlying area, extending west from Mishta-Shantish (Daniel Rattle) to the neighbourhood of the mouth Big Sango Pond, and north of Shankush (Sango Bay) to part of Merrifield Bay. This area covers about 80 km2, but it is obvious that only a small percentage of it must be considered. It consists mainly of present or former shorelines with a promising topography and good drainage.

9. Besides the three prehistoric sites that were discovered in the summer of 1996, four other prehistoric sites were already known in the study area: GlCg-1, GlCg-2, GlCh-1 and GlCh-2 (GlCh-1 being located southwest of Shankush [Sango Bay]). For those sites, we recommend the following:

- GlCh-1 is located approximately 5 km southwest of Natuashish. Only one flake of Ramah chart was discovered there. Consequently, no further recommendation is made concerning that site.

- GlCh-2 is located 2 km south of Natuashish, near the mouth of the inlet leading to Little Sango Pond. No evidence of prehistoric occupation was found there, but many historic and recent campsites were discovered. The survey recommended for the northern shore of Shankush (Sango Say) should determine whether any prehistoric artifacts occur in this area.

- GlCg-1 and GlCg-2 are located west of the Mishta-Shantish (Daniel Rattle), near its confluence with Shankush (Sango Bay). These sites were excavated in the mid 1980s, revealing many different levels of prehistoric occupation: Maritime Archaic, Late Prehistoric Indian, Point Revenge, as well as a cache containing Middle Woodland tools and numerous historic recent campsites. As for GlCh-2, the survey recommended (#8 above) along Shankush (Sango Bay) and Mishta-Shantish (Daniel Rattle) should determine whether the limits and components of these sites have been properly delimited.

10. Also for the construction period between 1998 and 2001, we recommend that an archaeologist be present at the site (see recommendation #7 above, for the 1997 season) to deal with unforeseen situations.

Other Issues

11. Burial sites should be subjected to special treatment. There are known instances of such sites, especially on the northern shore of Sango Bay (Whitford Env. Ltd, 1994:9). Their symbolic value greatly transcends the utilitarian context of dwellings. Also, a burial site should never be dug or excavated without an explicit agreement from the family of the deceased, from his/her descendants or, in the case of an anonymous grave, from the community itself. Should the occasion arise, a ceremony should be conducted in the presence of community members before any archaeological excavation is attempted.

12. Finally, before the season of 1997, the MIBC, the MIRC and the community elders should decide on the importance to be given to the historic and recent sites (Recommendation #4). Should they be given a fuller recognition, the archaeological survey should reflect this fact, and some form of cooperation should be initiated with the ethnologists that would collect testimonials on these sites. We have stressed that three of the recent sites already discovered seem to be the most promising (NAT-11, NAT-12, and NAT-18). In a future ethno-archaeological research program in the area, Borden numbers should be attributed to some of those recent sites.

“Tan eshinakushiak uipits unauitamau, the Heritage.” The development of Natuashish is considered as the first step towards settling a territory in fuller harmony with the traditional roots of the Mushuau Innu. For the young, who are the future of this community, this project must prove to be a way to alleviate the difficult social integration process that they live through presently. Being aware of their roots and the antiquity of their culture, and learning to know, respect, and value the ingenious ways in which their ancestors tamed a hostile environment are powerful tools that will help them find their place in the world.

There are two ways to consider the archaeological variable in a development context such as that of Natuashish:

- treat it as a non-renewable resource that must be protected from destruction in order to meet regulations, or

- integrate it to the development project itself, so as to give it even more value.

With the first option, archaeology is perceived as a step towards obtaining a construction permit, according to the second option, it is considered a treasured resource that can add positively to the project.

One way to smoothly integrate archaeology into the development project, so as to fully benefit from its cultural and scientific teachings, is through the preservation and display of the findings brought back to light by archaeological excavation:

… there is a growing interest among the Innu in preserving and displaying to children aspects of their traditional heritage. (Whitford Env. Ltd, 1995:81)

This leads us to this report’s last recommendation:

13. In order to ensure the community a fair return on its investment, and so that the whole population, and primarily the young, can admire and value the past of the Innu people, we recommend that an interpretation centre be built in the future community of Natuashish and be devoted to the preservation, popularization, and spreading of Innu prehistory and history. It is not a simple matter of displaying stone tools, but a whole museum concept that will lead to the understanding of all past aspects of the Innu cultural, economic, and social life, that of their ancestors, and that of other native people who settled this area. This interpretation centre would generate at least one permanent job for an Innu and be integrated into the children’s school curriculum. It could also display archaeological and ethnological artifacts from areas other than Shankush (Sango Bay) and Utshimassit (Davis Inlet), particularly from Voisey’s Bay, where much archaeological research is presently under way.

Note:

1 Length is defined as the maximum length along the axis of the hole, while the diameter is the maximum length measured perpendicularly to the axis.

References

Armitage, P.

1990 – Land Use and Occupancy Among the Innu of Utshimassit and Sheshatshit, Innu Nation, Nitassinan.

Benmouyal, J.

1987 – Des paléoindiens aux iroquoiens en Gaspésie: six mille ans d’histoire. Dossier no. 63, ministère des Affaires culturelles, Québec.

Chapdelaine, C.

1994 – “La place culturelle des paléoindiens de Rimouski dans le nord-est américain,” in C. Chapdelaine (ed.), Il y a 8000 ans à Rimouski… – Paléoé cologie et archéologie d’un site de la culture plano. Paléo-Québec no 22 – Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, pp. 267-277.

Clark, P.V. and W.W. Fitzhugh

1991 – “Postglacial Relative Sea Level History of the Labrador Coast and Interpretation of the Archaeological Record.” In L.L. Johnson (ed.), Paleo-shorelines and Prehistory: an Investigation of Method. C.R.C. Press, Boca Raton, pp. 189-213.

Denton, D.

1989 – “La période préhistorique récente dans la région de Caniapiscau.”Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, vol. XIX (2-3), pp. 59-75.

Ellis, C.J. and D.B. Deller

1990 – “Paleo-indians.” In, C.J. Ellis and N. Ferris, eds., The Archaeology of Southern Ontario to A.D. 1650. Occasional publication, of the London Chapter, Ontario Archaeological Society no 5, pp. 37-63.

Fitzhugh W.W.

1980 – “A Review of Paleo-Eskimo Culture History in Southern Quebec-Labrador and Newfoundland.” études Inuit Studies vol. 4 (1-2), pp. 21-45.

1978a – “Maritime Archaic Cultures of the Central and Northern Labrador Coast.” Arctic Anthrogology XV(2), pp. 61-95.

1978b – “Winter Cove 4 and the Point Revenge Occupation of the Central Labrador Coast.” Arctic Anthropology XV(3) pp. 146-174.

1972 – Environmental Archaeology and Cultural Systems in Hamilton Inlet, Labrador: A Survey of the Central Labrador Coast from 3000 B.C. to the Present. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, no 16.

Henriksen, G.

1981 – “Davis Inlet, Labrador,” in J. Helm (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 6: Subarctic. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 666-672.

1973 – Hunters in the Barrens, the Naskapi on the Edge of the White Man’s World. St. John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Hillaire-Marcel C. and S. Occhietti

1980 – “Chronology, Paleogeography and Paleoclimatic Significance of the Late and Post Glacial Events in Eastern Canada.” Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie 24. pp. 373-392.

Keenlyside, D.L.

1985 – “La période paléoindienne sur Îlle-du-Prince-édouard.” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec XV(1-2). pp. 119-126.

Loring, S.

1989 – “Une réserve d’outils de la peacuteriode Intermédiaire sur la côte du Labrador.” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec XIX(2-3). pp. 45-57.

1988 – “Keeping Things Whole: Nearly Two Thousand Years of Indian (Innu) Occupation in Northern Labrador,” in C.S. Reid, ed., Boreal Forest and Sub-Arctic Archaeology. Ontario Archaeological Society Inc., no 6. pp. 157-182.

1984 – “Archaeological Investigations into the Nature of the Late Prehistoric Indian Occupation in Labrador: A Report on the 1984 Field Season,” in J.S. Thomson and C. Thomson, eds., Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1984. Historic Resources Division, Department of Culture, Recreation and Youth, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. pp. 122-153.

MacDonald, G.F.

1985 – Debert: A Paleo-Indian Site in Central Nova Scotia. Buffalo, NY: Persimmon Press.

McCaffrey, M. T.

1989 – “L’acquisition et l’échange de matières lithiques durant la préhistoire récente: un regard vers la fosse du Labrador.” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec XIX (2-3). pp. 95-107.

Mailhot, J.

1983 – à moins d’être son esquimau, ont est toujours le Naskapi de quelqu’un.” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec XIII(2). pp. 85-100.

Nagle, C.

1978 – “Indian Occupations of the Intermediate Period on the Central Labrador Coast: a Preliminary Synthesis.” Arctic Anthropology XV(2). pp. 119-145.

Newfoundland Geosciences Ltd.

1994 – “The Identification and Investigation of Borrow and Aggregate Sources in the Sango Bay Area, Labrador: Phase II Report.” Submitted to Mushuau Innu Renewal Committee, c/o Paul F. Wilkinson and Associates Inc., Montreal.

Pintal, J.-Y.

1989 – “Contributions à la préhistoire récente de Blanc-Sablon.” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec XIX(2-3). pp. 33-34.

S.A.G.M.A.I. (Secrétariat des activités gouvernement tales en milieu Amérindien et Inuit)

1984 – Nations autochtones du Québec. Québec.

Samson, G.

1983 – Préhistoire du Mushuau Nipi, Nouveau-Québec: étude du mode d’adaptation a l’intérieur des terres hémi-arctiques. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto.

1978 – “Preliminary Cultural Sequence and Paleo-Environmental Reconstruction of the Indian House Region, Nouveau-Québec.” Arctic Anthropology XV(2). pp. 186-205.

Speck, F.G.

1977 – Naskapi: The Savage Hunters of the Labrador Peninsula. Normand: University of Oklahoma Press.

Turner, L.M.

1979 – Ethnology of the Ungava District, Hudson Bay Territory: Indians and Eskimos in the Quebec-Labrador Peninsula. Québec: Presses Comeditex.

U.M.A. Group

1994 – Natuashish: Little Sango Pond Community Concept. Submitted to Mushuau Innu Band Council and Mushuau Innu Renewal Committee.

(Jacques) Whitford Environment Ltd.

1994 – “Phase 1 Report on the Heritage Study for Utshimassit Community Relocation Progect, Sango Bay Area, Labrador.” Submitted to Mushuau Innu Band Council and Mushuau Innu Renewal Committee, c/o Paul F. Wilkinson and Associates Inc., Montreal.

1995 – “Utshimassit Relocation: Initial Environmental Assessment, Final Report.” Submitted to Paul F. Wilkinson and Associates Inc., Montreal.